The Great Depression of the 1930s hit Canada especially hard. The fledgling nation was largely a producer of raw materials and depended greatly on the export of goods to other nations. Those nations were also struggling economically and couldn’t buy our products.

The result was that 30 per cent of the Canadian work force was unemployed by 1933. Very little in the way of a social safety net yet existed, so those who were jobless had to find their own way of surviving.

Wages dropped in the 1930s, but prices dropped even more. The more affluent citizens actually saw an increase in their standard of living, as their dollars had more buying power than ever.

Anyone who had been barely getting by prior to the economic crash had little hope of improving their situation during those harsh depression years. Uneducated labourers, small farmers, single men and those with any kind of disability suffered badly.

If the economic situation was bad, the stigma attached to being unemployed and rootless was worse. The local newspapers were filled with the stories of misadventures involving transients (the nicer of the usual terms used), hobos and bums.

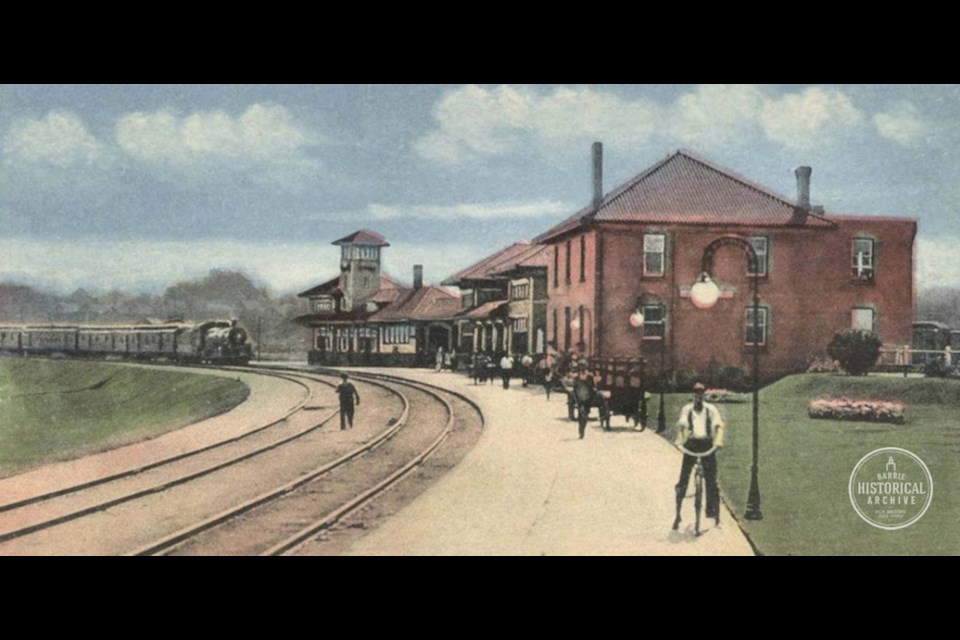

At the eastern edge of the Allandale railway lands near Minet’s Point, there arose a community of the less fortunate that was known locally as ‘The Jungle’. It was a handy spot in some shady woods, close to the water and near to the tracks which afforded some free but illegal transportation.

This encampment was both loathed and feared by many in Barrie. Folks took the long way around when walking in the area and most petty crimes nearby were blamed on the inhabitants.

The Barrie Examiner reported on Sept. 27, 1934 that Burton Avenue United Church held a wiener roast for its young people’s group near the White Oaks estate in the Minet’s Point vicinity.

“The 45 present enjoyed a very delightful outing with games etc. The close proximity of the ‘Jungle’ was a great factor in keeping the crowd close to the bonfire.”

During the summer months, more than a few people were lured into the crystal blue waters of Kempenfelt Bay on a hot day only to find their belongings gone when they arrived back on the beach.

In July 1939, two Toronto teens who had jobs in a Gerrard Street fish monger shop, saved up a little money and decided to take a jaunt into the Canadian wilderness north of the city and rough it for a week. They got as far as St. Paul’s on their savings and then walked towards Barrie. The two settled with their camping equipment and cooking utensils into a little corner of the forest on the south side of the bay, in that place known as The Jungle.

“This particular place is the favourite rendezvous for transients and bums and is often cleared of its inhabitants by police. The young men had their supper about 6:30 Monday evening and, donning their bathing suits, and hiding their $35 in the toe of one of their socks, they tucked their clothing and knapsacks under a bush, they trotted down the beach to the Allandale dock, where they swam for an hour or so.”

The July 27 edition of the Northern Advance went on to describe the shock the boys got when they returned to that bush dripping wet and found their possessions gone. All they could do was call the police, which they did. Young Ted O’Halloran and Douglas Lambie were brought to a local hotel to be housed and fed for the night. The next day, their parents arrived to rescue and clothe them.

Not surprisingly, no trace of any disappeared objects ever turned up.

The railway employees were kept busy with the antics of the Jungle residents. They were constantly on the alert for thefts, unauthorized entry into buildings and rolling stock and the presence of persons who might be injured if they got too close to moving trains.

In May of 1935, a boarding car was found to have been entered and several woollen blankets taken. C.N.R. constable Charles Fullerton and Barrie Police Chief Alex Stewart made a search of the Jungle area. Twelve inhabitants were there but no stolen blankets. A middle-aged man was seen walking in the area about 3 a.m. and so he was arrested on suspicion of the theft. Magistrate Jeffs offered the accused a $10 fine or 10 days in jail. He chose jail.

Constable Fullerton and Chief Stewart were called to the Jungle area again on May 1938, and likely on many other occasions as well. This time, “eight old ‘uns” as the Northern Advance called them, arrived in Barrie and proceeded to celebrate that milestone by consuming large quantities of liquor. Feeling very jovial, the group decided to carry on and to continue the party on a freight train bound for more northerly destinations.

Naturally, C.N.R. brakeman, William Lee, objected to their mode of travel but was outvoted and outnumbered. As the train began to pass the front of the Allandale Station, Lee was unceremoniously thrown off the slow-moving train. Of course, the train was stopped and the partiers detained.

The charges dished out by Magistrate Jeffs varied from unlawful entry of a railroad train to breaches of the Liquor Control Act. Once again, the choice was $10 or 10 days. Not surprisingly, 10 days was the more popular of the two options.

Each week, the Barrie Historical Archive provides BarrieToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past. This unique column features photos and stories from years gone by and is sure to appeal to the historian in each of us.