This story by Chris Tenove, of University of British Columbia originally appeared on The Conversation and is republished here with permission:

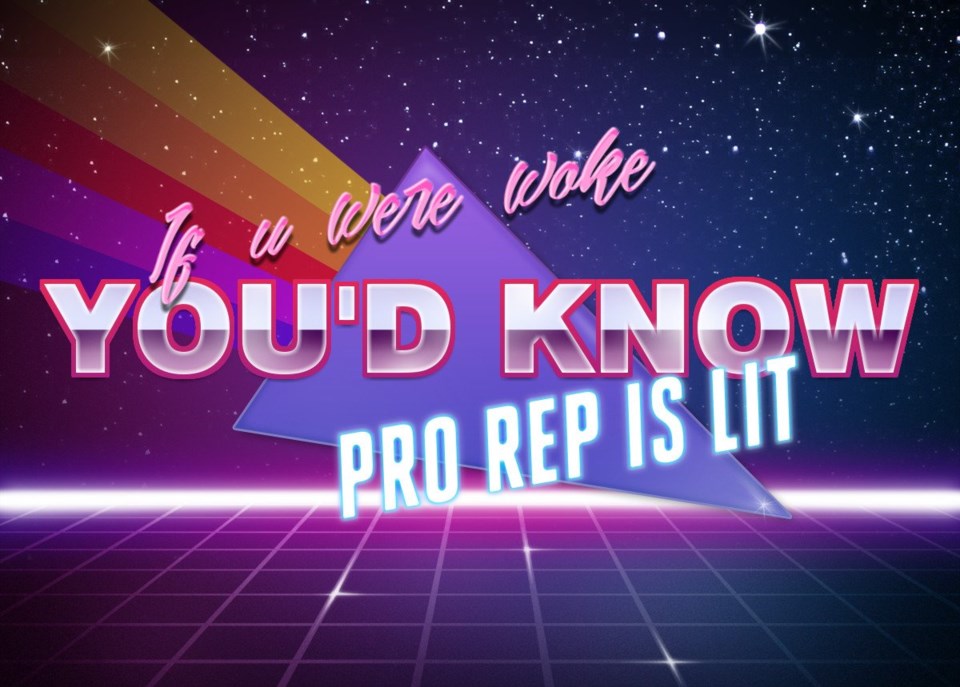

In November, during a televised debate about electoral reform, British Columbia Premier John Horgan told the audience, “If you were woke, you’d know that pro rep is lit.”

By “pro rep,” he meant “proportional representation,” an alternative to the current first-past-the-post voting system. By “woke,” he meant socially conscious. By “lit,” he meant, according to the Urban Dictionary, “Something that is f—ing amazing in any sense.” The B.C. NDP soon tweeted his remark, and a meme was born.

#pr4bc #prdebate #yepprorep pic.twitter.com/vimMefto0a

— BC NDP (@bcndp) November 9, 2018

This is a federal election year, so Canadians should be ready for a meme-filled 2019. Political memes are increasingly prominent in political discourse, and politicians will be using this latest online strategy to attract, infuriate, persuade or bemuse voters.

It’s therefore worthwhile understanding how memes can shape the tone and perceptions of campaigns or policies. And it’s also useful to look at politicians’ recent attempts to use memes for good and ill.

What is a political meme?

A political meme is a purposefully designed visual framing of a position. Memes are a new genre of political communication, and they generally have at least one of two characteristics — they are inside jokes and they trigger an emotional reaction.

Memes work politically if they are widely — or virally — shared, if they help cultivate a sense of belonging to an “in-group” and if they make a compelling normative statement about a public figure or political issue.

Memes can spread rapidly online and into popular culture due to their shareability — they are easily created, consumed, altered and disseminated. They can quickly communicate the creator’s stance on the subject. The stronger the emotional response provoked by a post, the greater the intent to spread it.

Though memes may spread widely, they usually cater to a specific audience who inhabit a “shared sphere of cultural knowledge.” That audience tends to have self-referential language, cultivating an in-group that can decipher the memes and get the “in joke” while those who aren’t in on the joke cannot. (For an excellent display of this, listen to one of the “Yes Yes No” segments on the Reply All podcast, in which the hosts explain complex, multi-layered memes to a confused non-digital native.)

A person who wants to successfully create or repurpose a meme therefore needs to have sufficient understanding of that shared sphere and its digital norms.

By drawing on shared meanings, meme creators can compress complex ideas into simple visual packages. For instance, feminist memes both critiqued and lampooned the 2012 claim by presidential candidate Mitt Romney that he had “binders full of women” that he could bring into his administration.

‘I have a drone’

Memes about former president Barack Obama’s administration ranged from silly emotions to ones that challenged the dominant political discourse, such as the critique of his targeted drone program through the “I have a drone” meme.

Similarly, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has been the focus of many positive memes, particularly when he is compared to U.S. President Donald Trump, but also negative memes, including those referencing Canada’s arms deal with Saudi Arabia.

The dark side of memes

While memes can communicate nuanced ideas, generate a sense of cultural belonging and evoke strong emotions, they also have serious downsides as forms of political discourse. Political memes can offer deeper reflections on social issues, with a persuasive effect that risks creating “a self-convincing audience” that is motivated to engage with the messaging.

There is serious concern that memes are replacing the nuanced debate necessary in a healthy democracy.

It is still debated whether racist, “alt-right” memes, many originating on Reddit and 4Chan with an increasingly transnational reach, were a deciding factor in Trump’s 2016 election win.

Authoritarian regimes are also reported to have co-opted online political humorous content, especially memes, both domestically and abroad to advance their interests.

Furthermore, seemingly neutral memes can be “weaponized”. An infamous example is Pepe the Frog, which evolved from a sad frog cartoon into a symbol for the politically charged, racist and anti-Semitic messages of the so-called alt-right, a U.S.-based white nationalist movement.

Another means of weaponization is to link politically charged issues like immigration or climate change to unrelated but highly provocative issues like the spread of the Zika virus.

It can be difficult to counter these negative effects of memes. One problem is that they can rarely be fact-checked. Rather than making textual claims, they rely on a visual grammar. After all, it would be silly to fact-check an electoral system equated to Oprah’s gift giveaways.

Because memes are ambiguous and require interpretation of visual grammar, it is hard to hold their creators to account. For instance, when people are called out for creating or spreading memes that symbolise white nationalism, they can deny the given meaning, or state that it is a joke.

Should politicians meme?

Politicians are therefore playing with fire when they try to get in on the mainstreaming of memes. They risk being perceived as making lame attempts to cater to a community to which they do not belong. Hillary Clinton’s attempt to engage young voters backfired when she tweeted out “How does your student loan debt make you feel? Tell us in 3 emojis or less.” It was criticized as condescending and a distraction from her actual policy proposal to make college more affordable.

Politicians can face ridicule and accusations of “inauthenticity” when they engage in this new form of political performance.

When politicians use memes, they must also surrender control over how they will be repurposed and interpreted over time.

Premier Horgan did not say “pro rep is lit” because it was a convincing argument, but because he knew it would get the internet’s attention.

Politicians need to connect with young voters, and use memes to signal to this particular demographic. Pro Rep advocates in B.C. created a meme contest because they recognized connecting with young voters is a top priority as youth are more likely to be in favour of proportional representation.

More research is needed to understand the effect that political memes have on the quality of political debate. In the meantime, politicians should be cautious — or risk becoming this guy:

This article was co-authored with Grace Chiang, political science major at UBC

Chris Tenove, Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Political Science, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.