This is August 10, 1927. The liquor store doors are open, but will you venture in? For many years, the purchase of any kind of alcohol has been illegal in Ontario and now the government has eased those regulations.

What will your friends, neighbours, employer and clergyman think if you are seen making a purchase?

This is October 17, 2018. Unless you are over 100 years old, you likely will not remember a time that cannabis was legal anywhere in Canada. This green prohibition, which officially ends today, began in April of 1923. Lumped in with opium, morphine and cocaine, a new federal bill under the King government sought to proscribe three additional substances: codeine, heroin and cannabis.

Our mixed feelings of interest, curiosity, confusion and hesitation surrounding marijuana today must be very similar to the emotions felt by the Barrie folks of 1927, when legally sold alcohol suddenly returned to the town.

Before the days of the so-called social safety net, drinking alcohol in large amounts caused families untold grief. Parents who drank spent a lot of the family’s income on liquor, leaving great poverty at home, while causing domestic upheaval, frequent visits to the Barrie Jail, lack of steady employment and generally ruined lives.

Clergy and various temperance groups agitated for the complete ban on sale and consumption of alcohol during the late 1800s. They nearly succeeded in 1898 when a plebiscite under the Laurier government showed that a majority of Canadians wanted a dry country, but the vote was not seen as a clear enough indication that the nation was quite ready yet for a full liquor ban.

That sentiment changed in 1916 when Great War patriotism gave the provinces the support they needed to enact a law that closed drinking establishments and ended the sale of alcohol. Most folks in Barrie, and elsewhere in Canada, saw this as a sacrifice that they should make while their sons and brothers were away and fighting in foreign fields.

On the eve of this event, the ‘Northern Advance’ of Sept. 28, quoted another publication, the ‘Simcoe Reformer’.

“We are generally inquisitive as to how much of its brilliant promises prohibition can fulfil. If it can banish sickness, poverty and crime, as it advocates, no one will ever vote for its repeal. On the other hand, if the law is bad, its enforcement will sooner compel its abandonment for something better.”

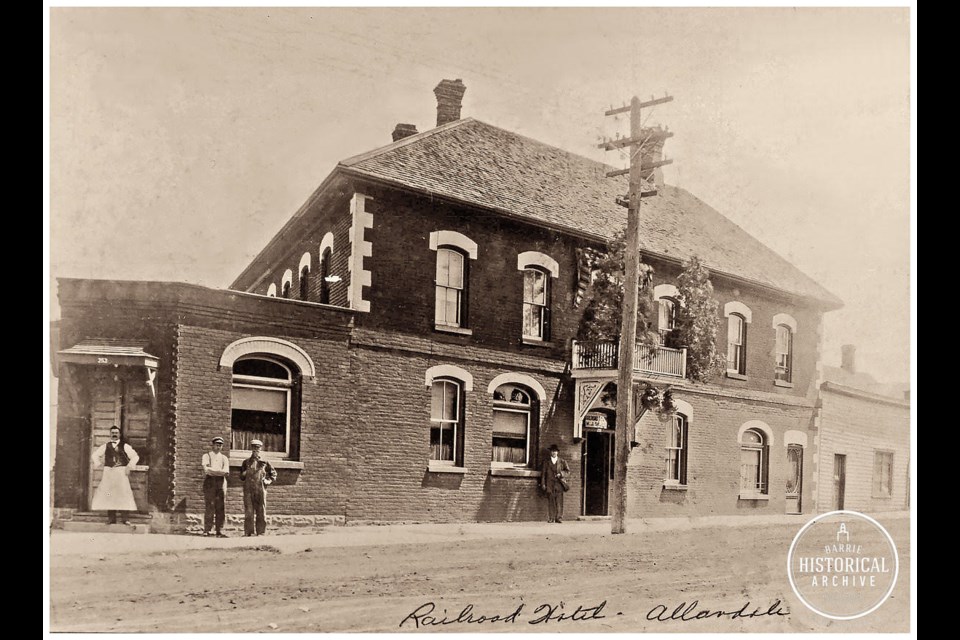

The hotels of Barrie had a new reality to deal with that autumn. Their liquor licenses were gone and they were forced to apply for a new license that allowed them to sell soft drinks, cigars, tobacco, ice cream and a light 2.5-per-cent beer. The Clarkson, American and Barrie Hotel took the new arrangement in stride while some others struggled to adjust.

The fate of the Wellington Hotel was then up in the air. It had already fallen on hard financial times and was in the hands of the Sheriff’s Office in 1916. Owner, Hunter Kennedy, was considering converting the ground floor to shops.

The Simcoe Hotel had returned to the hands of John Ness who had been hotelier there thirteen years earlier. He had retired from the often wild west life of liquor purveyor but decided to take a chance on running a tamer version of the old Simcoe. Ness had nearly caused the demolition of the Simcoe that year as he considered selling the site to the Bell Telephone Company which was looking for a place to build. Lucky for the old gal, Bell had already arranged another lot.

What was called the ‘noble experiment’ by some, lasted in Ontario for eleven years. Stiff penalties and social stigma only drove the liquor trade underground. Swamp whiskey men popped up everywhere and distilled their moonshine in every isolated corner of the province, including many who supplied the Barrie area. Speakeasies could be found, by those with connections, in the backs of shops and barns.

Of course, there was always the doctor. By 1924, Ontario physicians were prescribing nearly a million doses of alcohol a year as their right to use it as a curative had never been rescinded.

Little by little, support for prohibition in Ontario eroded. There were so many loopholes in the law that the Act began to look like a joke, rum running to the U.S. during its prohibition years drastically increased cross border smuggling, and tragic accounts of tainted moonshine deaths were often reported.

By 1919, Canada had repealed its prohibition act on the federal level. The individual provinces, which had been given the control to oversee how alcohol was to be distributed, all remained ‘dry’ with the exception of Quebec. The Ontario Temperance Act stood up to referendums in 1919 and 1921. In 1924, under the premiership of George Ferguson, another vote showed that there was little desire for continuing the ban of alcohol sales in Ontario. However, nothing really changed for three more years.

Finally, with the creation of the Liquor Control Act of 1927, government run depots for the sale of alcoholic drinks were opened in communities that wanted one, and only if that community was deemed suitable. We know them as the ‘Beer Store’ and the ‘Liquor Store’ today.

Did the saloon doors swing open that day as well? No, the barmen of Barrie and their thirsty patrons had to wait another seven years for that to happen. Until 1934, those in need of a drink required a permit to be presented at the liquor outlet, identification produced, order forms filled out and the goods slipped into a closed plain brown paper package for transport home.

On July 26, 1934, the ‘Northern Advance’ reported this piece, which may well have cheered up the locals on what was likely a hot summer day in Barrie.

“Thirsty citizens are able to quench their thirsts at four local hotels this week, where beer is served under the new regulations of the Liquor Control Board. So far the beverage is only sold in bottles 15 cents per pint or 25 cents a quart. It is expected that draught beer will be available by the end of the week. A brisk trade is being done by all four hotels but no drunkenness has been noticed as yet.”

Each week, the Barrie Historical Archive provides BarrieToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past. This unique column features photos and stories from years gone by and is sure to appeal to the historian in each of us.