In 1877, live music was the only form of music available to the citizens of Barrie. Anything else was unimaginable at that time.

No opera house or music hall yet existed in the town. Performances, other than home produced entertainment, were limited to the church, or at special events put on by local bands, the town or fraternal organizations.

Yet, in far off France, a group of scientists had found a way to capture sounds waves and that theory inspired inventor Charles Cros to develop a way to play those sounds back again by tracing the sound wave patterns onto a metal surface and by using a stylus to reanimate them.

This discovery was eclipsed by the unveiling of Thomas Edison’s much celebrated phonograph at about the same time.

The invention of the phonograph did not excite music lovers much in those early years. Its intended purpose was far more mundane. The phonograph was originally a piece of office equipment and the main commotion surrounding its introduction was the fear that it would lead to the extinction of the stenographer.

At nearly the same time, Alexander Graham Bell was working out the kinks of his graphophone, which employed cardboard and wax cylinders to save the sounds, as opposed to Edison’s foil covered cylinders.

The more commonly heard term gramophone started out as a brand name for the so-called talking machines, but is now used as a generic word for these early recoding devices.

By 1900, Barrie folks might experience the wonders of a phonograph if one was brought to town as part of a community occasion or as part of an exhibition.

Ads then began to appear in the local newspapers, which promoted the phonograph as an entertainment centre for the whole family, something that could provide endless “songs, marches and funny stories” from $5 to $150. A luxury item, to be sure.

In the first decade of the 20th century, the cylinder system co-existed with the new disc record system that we know today.

Those earliest records were made of a combination of shellac, mineral powder, fabric and oil. They were quite breakable.

The value of having music on hand at all times became apparent as the Great War approached. No longer did the Barrie consumer have to send away to New York City for their own parlour phonograph after local merchants, who weren’t slow to see the trend, began to sell them in their shops.

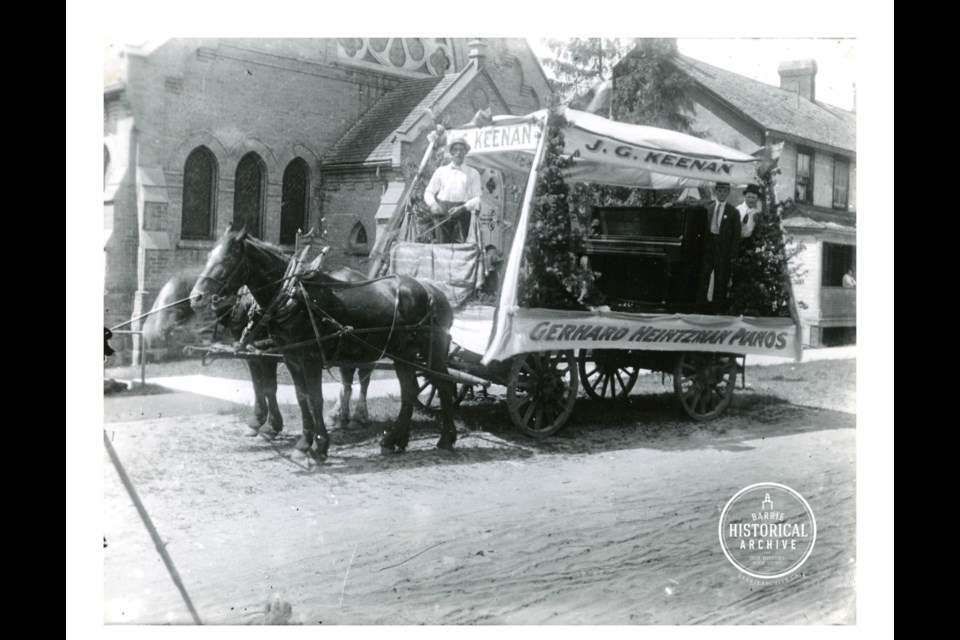

James G. Keenan had bought out Carson’s barber shop at 62 Dunlop St., in 1900. He cut hair, but kept his business well diversified by selling cigars, violins, banjos and guitars at the same time.

In 1910, he put down his scissors to concentrate solely on the musical end of his enterprise. Keenan became one of the first dealers in home use phonographs in Barrie.

He was in good company. Garrett’s Music Shop was a competitor as was J.M. Greene and Patterson’s in Allandale.

Mr. Keenan passed away in 1946, after having expanded the business and moved to 54 Elizabeth St., and then to 24 Elizabeth St.

In 1949, his wife and daughter relocated the music store across the street to a spot close to the Bank of Nova Scotia at Five Points.

Mrs. Keenan died in 1960. The store continued on under the direction of her daughter and son-in-law.

For a long time, Keenan’s Music Store at Five Points was the go-to place for pianos, sheet music and the latest vinyl record.