A Barrie mystery, now nearly 91 years old, may finally be solved thanks to the availability of family history-related records held by various genealogy websites, something that definitely wasn’t possible in 1927.

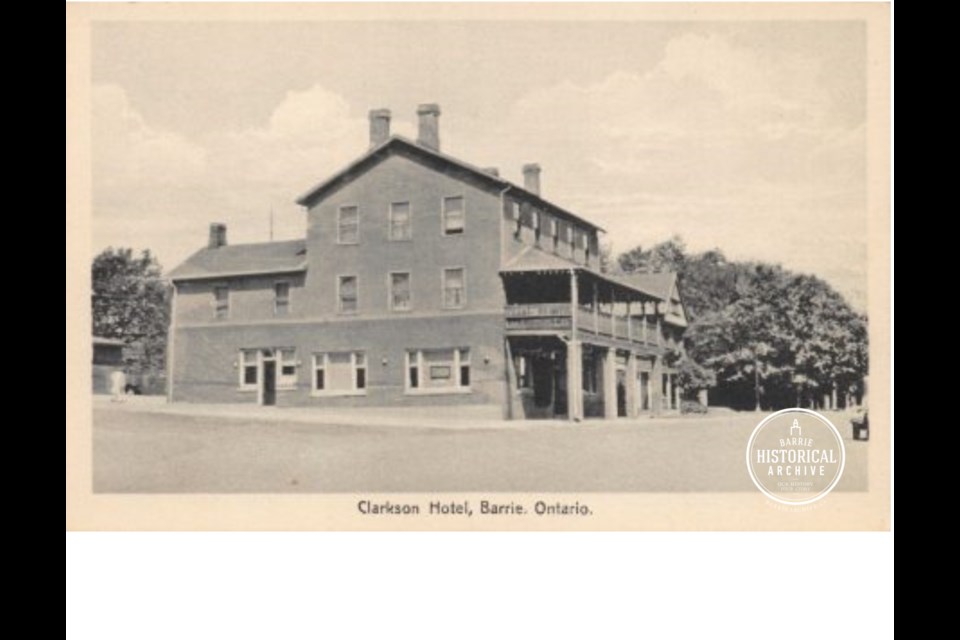

Perhaps Thomas Baggs didn’t care to do his own cooking, housekeeping and laundry. The unmarried, middle-aged Canadian National Railway (CNR) worker had long ago saved enough money to purchase and fully furnish a house on John Street, but he spent just one night under its roof. It stood empty for over a decade while he enjoyed room and board in the Clarkson Hotel.

Mr. Cubitt-Nichols, proprietor of the Clarkson, knew Baggs to talk to, but not terribly well. He was aware that Thomas Baggs was an Englishman, born in the neighbourhood of 1874, who had come to Canada in the first years of the 20th century.

Thomas Baggs was a war veteran who spoke of seeing action in India, Gibraltar and South Africa.

Thomas Baggs kept to himself and largely remained in his room when not working. He made no friends and he never took a wife.

On Christmas Day 1927, Thomas Baggs took ill. Mr. Cubitt-Nichols arranged for Dr. Turnbull to come and have a look at his ailing boarder. The doctor advised a trip to the hospital, but Thomas Baggs was having none of that. Instead, medicine was left at the hotel and, just before midnight, the hotelier placed it and a pitcher of water at the patient’s bedside.

Come morning, Thomas Baggs was dead.

The Brotherhood of Railway Trainmen took care of the funeral arrangements. After the burial at Barrie Union Cemetery, two of Baggs’ fellow workers and Mr. Cubitt-Nichols searched the deceased’s room for an address book, a will or letters ... anything at all that might lead them to the whereabouts of any family members.

They found nothing.

The John Street house similarly contained no clues.

What was found was money. Thomas Baggs had been squirreling it away for years. In fact, the dead man’s pocket held $435 in cash, which today is worth closer to $7,000.

With no will or family to be contacted, it appeared likely that his property and money would be turned over to the Crown. Probably, that is exactly what happened.

Somewhere on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, a family may have wondered what became of their son and brother. Single immigrant men weren’t known to be particularly good at writing letters home, so it wouldn’t be unusual for families to eventually lose touch completely. Surely, though, somebody must have thought of Thomas from time to time.

This story, dubbed the ‘Mystery Man’ by the Northern Advance, quickly went quiet as there was little chance of any more progress being made unless a relative should appear or write to inquire about Thomas. That doesn’t seem to have happened.

Earlier this week, as I began researching the history of the Clarkson Hotel for a local history project, I came across the tale. Knowing what fantastic online resources are out there today, I thought to myself – this mystery can probably be solved now!

It didn’t take long. Two hours, in fact. Using the clues that Thomas Baggs had given Mr. Cubitt-Nichols so long ago, it became apparent that a man from Hammersmith, England matched his description.

His full name was Thomas Ernest Cecil Baggs and he was the son of railway clerk, Alfred Baggs, and his wife, Martha. He grew up on a street called Hammersmith Grove in this London district, a short walk from a fair-sized railway hub at which both Thomas and Alfred were likely employed at times.

Born in 1873, Thomas Baggs had an older brother, Harold Edgar, and a younger brother, Alfred Everyn.

When he was 21 years old, Thomas enlisted in the military and signed on with the Manchester Regiment, Second Battalion. Indeed, he had been involved in all of the war theatres that he had spoken about to his innkeeper. He was credited for 12 years of service — eight of which were spent in action in foreign lands — and given a pension.

Soon afterwards, Thomas immigrated to Canada.

Just before the outbreak of the Great War, Canada had the strongest economy in the world. Everything was booming. Construction was constant everywhere, land was being cleared, railways were expanding in every direction, and mines and lumber camps were crying out for workers. It was the ideal time for a man like Thomas Baggs to make a fresh start.

During his years away from home, Thomas’ parents had died and his brother, Harold, married but appears to have had no children. Oddly, it would seem that Thomas must have had some brief reacquaintance with his youngest brother, Alfred, who had immigrated to Canada himself in 1912 and settled in nearby Bradford, only to disappear again when he joined the Canadian Expeditionary Forces at the start of the Great War.

Alfred, while on leave in England in late-1915, requested and received permission to marry. When the war ended, Alfred chose to remain in England with his new wife.

Both of Thomas Baggs’ brothers survived him by quite a few years. Edward passed away in 1944, and Alfred in 1968. Did they ever hear of Thomas’ passing, or where he is buried, and did they receive any of his estate?

We now know who he was, but more of his story remains to be written.

Thomas Baggs’ youngest brother did marry and had a family. Descendants of Alfred Everyn Baggs, are you out there somewhere?