What do you picture when you think of the Ku Klux Klan?

Likely, you think of a group of bigoted fanatics in white robes and hoods, centred in the American south, carrying out their cause of promoting all things white and Protestant.

You might be surprised to learn that the reach of the KKK spread north of the border, and at the height of their national popularity, the most infamous of their Canadian actions occurred right here in Barrie.

The Klan was born immediately after the American Civil War when returning Confederate soldiers found their way of life forever changed and they put the blame largely on freed black men and their sympathizers. The United States government had no patience for continued violence in the South and so the KKK was outlawed in 1871.

The Klan re-formed just after World War 1. So-called ‘ordinary Americans’ were becoming very concerned about their communities and their jobs in the face of mass immigration from Europe. Black Americans were slowly being allowed more rights. Many white Americans saw the Klan as the guardians of their way of life and joined in huge numbers.

At the same time, enough Canadians were worried about seeing this country lose its ‘Britishness,’ meaning increased ethnic and religious diversity, that KKK chapters formed here too in the 1920s.

The KKK in Canada attempted to set itself apart from their American counterparts by denouncing lawlessness and violence.

However, the Klan would forever regret their expansion into the Town of Barrie because it was here that their movement started its rapid decline into unpopularity.

His father had sent him away. William Skelly was in his late twenties but had already lived a lifetime of troubles. In his native Northern Ireland, he had witnessed sectarian violence including the death of a girl he had loved. Skelly fought for Britain in the Great War and had been badly wounded, resulting in the metal plate now protecting his skull. He married but it seems he was charged with assaulting his wife. Other charges included drunkenness and assaulting a police officer. A fresh start was in order.

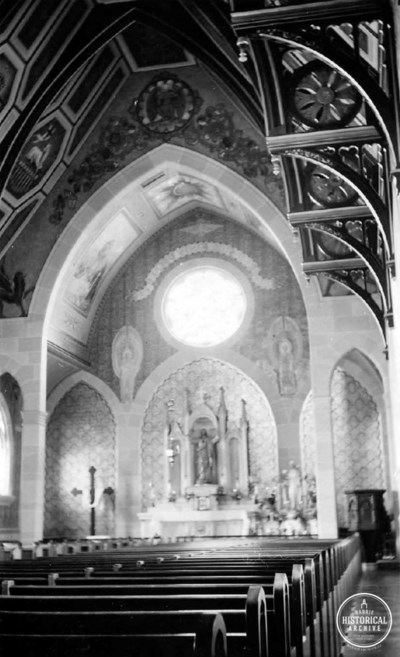

The interior of St. Mary's circa 1950. Photo courtesy of the Barrie Historical Archive.

The interior of St. Mary's circa 1950. Photo courtesy of the Barrie Historical Archive. The young Irishman jobbed about in Ontario for many months before arriving in Simcoe County. He worked for a farmer in Innisfil for a time before finding employment with A.J. Tuck in his junk store on Dunlop St. in Barrie. Far from home, friendless and having no real prospects, William Skelly was ripe for the picking when the Ku Klux Klan brought their road show to town in June 1926.

On a hill, more or less where the Travelodge hotel stands at Bayfield St. and the 400, an eighty-foot cross was set on fire and was seen for miles around. It attracted the disenfranchised young man and he became a member of the Klan that night.

William Skelly first met William Butler, a local young man about his own age, who was Kleagle, or membership recruiter, of the Barrie klavern. In turn, he came to know Clare Lee who was klavern secretary and a co-worker of Butler at the shoe factory where both were employed.

Quite quickly after becoming acquainted, the three Klansmen decided that they needed to perform some sort of action to cement their commitment to the ideals of the Klan and, at first, chose the Champlain monument in Orillia for a demonstration of their dedication. It was a symbol of Roman Catholicism, or so they believed, and as such was counter to what they thought the KKK stood for.

Skelly took a revolver from his employer’s shop and purchased bullets, dynamite, fuse and blasting caps at a local hardware store on June 10, 1926. The trio was unable to find any means of transportation to Orillia, but their determination to make a clear anti-Catholic statement that day was unwavering and so they settled on something nearby. Skelly, Butler and Lee decided to blow up St. Mary’s Catholic Church.

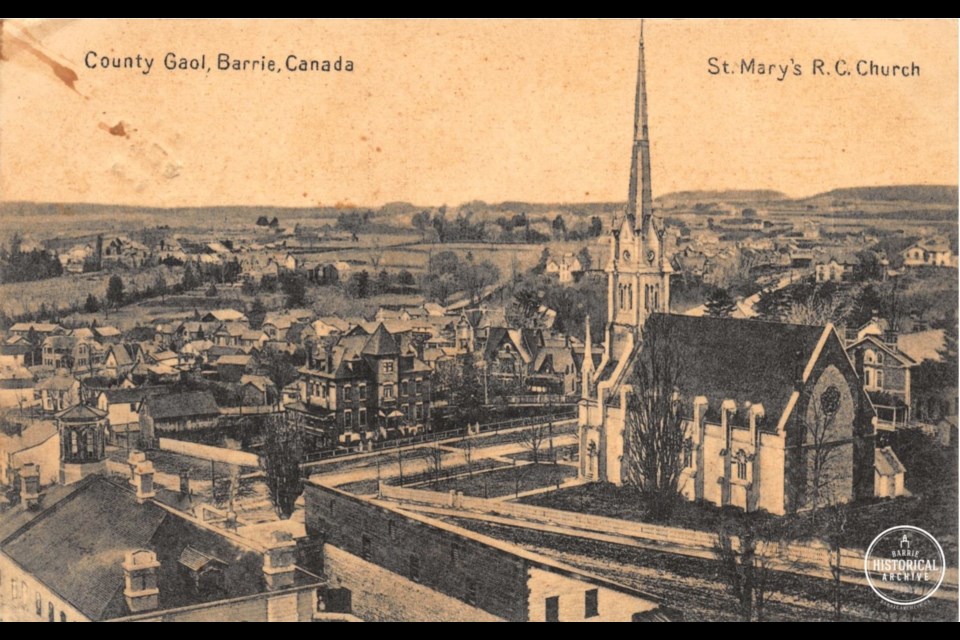

St. Mary's Catholic Church circa 1880. Photo courtesy of the Barrie Historical Archive.

St. Mary's Catholic Church circa 1880. Photo courtesy of the Barrie Historical Archive. Just after 6:00 a.m. on Friday, June 11, the church caretaker, Mr. LeClair, arrived at St. Mary’s and found a door on the north side of the building wide open. He was shocked to find that some kind of explosion had occurred, blowing a hole 4 feet around in the floor in the area of the centre aisle, and had sent chunks of wood flying through stained glass windows, broken light fixtures and shattered floor joists.

The police were called and almost immediately identified a piece of time fuse left at the scene. The act was called variably an ‘outrage’ and a ‘desecration’ in Barrie papers, and the local police began an intense but short investigation into who could have done this. A visit to a hardware store quickly pinpointed a suspect – the Irish chap working at A.J. Tuck’s shop.

When staying in Barrie became too hot a prospect, Butler and Lee helped him get away to Toronto. Skelly was at first helped by Klansmen there but they soon decided that he should be handed to the authorities and that the Klan should immediately cut ties with him.

William Skelly was arrested at King and Yonge St. in Toronto about 10 days after his crime, given up by Klan organizer, Major Proctor. He carried a letter, that he had been instructed to sign, stating that the attack on the church was all his idea and had nothing to do with the Klan.

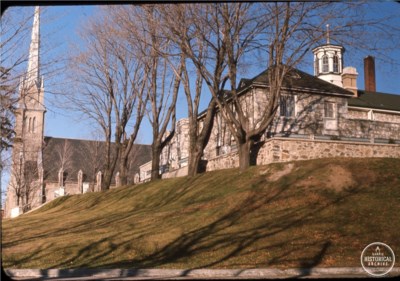

After his arrest for his attack on St. Mary's, William Skelly was housed next door at the Barrie Jail, 1967. Photo courtesy of the Barrie Historical Archive.

After his arrest for his attack on St. Mary's, William Skelly was housed next door at the Barrie Jail, 1967. Photo courtesy of the Barrie Historical Archive. Skelly was brought back to Barrie and lodged in the Barrie Jail. At the courthouse, he was eager to confess, lay out the whole sordid tale and easily implicate his accomplices, Butler and Lee. The townsfolk, who had been aghast at the crime committed by this outsider and the hate group from the south, were taken aback by the involvement of two local sons.

William Skelly was assessed by a psychiatrist in August of 1926 and, although the deed was an exercise in madness, Skelly was deemed fit for trial. As the trial approached, he offered to plead guilty but Justice Logie refused to accept the plea and moved for a full court hearing.

That third week of October, the trial began with standing room only and reports of curious citizens peering in the courthouse windows when they couldn’t get a seat inside.

The court heard that the three men drew paper scraps to see which of them would carry out the mission, and that Skelly drew one depicting a fiery cross which gave him the assignment. Lee showed him where the church was located and how to get into it. After fortifying Skelly with some dandelion wine, his co-conspirators sent him of to do the deed.

Skelly set his explosives on the top of a brick wall running north-south in the church basement and lit the fuse. He ran away and fired one shot of the revolver to alert Lee, who lived nearby, that the thing was done. Next came the sound of the explosion, which sounded innocuous enough to those who heard it, much like the backfire of a car.

In the end, all three were found guilty and sent to Kingston Penitentiary. Skelly drew the harshest sentence of four years at hard labour with a recommendation from Justice Logie that he be deported at the end of his sentence. The Justice had a few words to add in closing.

Looking at a house on the corner of Mulcaster and Codrington Sts. across the empty lot where St. Mary's once stood, 1974. Photo courtesy of the Barrie Historical Archive.

Looking at a house on the corner of Mulcaster and Codrington Sts. across the empty lot where St. Mary's once stood, 1974. Photo courtesy of the Barrie Historical Archive. “In this country, I am told, for many years Catholics and Protestants have lived in amity, side by side, never troubling each other. That is as it should be. We do not want in this country conditions which formerly prevailed in that distressful isle, Ireland, nor do we want those conditions – if the press is to be believed – which prevail at the present moment in the republic to the south.”

Afterwards, the Ku Klux Klan was held in very low esteem by the outraged Canadian people, both for its hateful mandate and for shaping a lost immigrant into a criminal and then turning their backs on him. The KKK quickly lost any favour they had built up in this country after that.