When three desperate criminals broke out of the Barrie Jail in 1931, turnkey John R. Weaymouth was celebrated as a hero.

Eight years later, just one man escaped and Weaymouth lost his job.

The Weaymouth name is deeply rooted in Barrie and very well known. John Rankin Weaymouth’s father, also John, came to here in 1851 as an adventurous teen. He may have been as young as 13 years of age when he began driving teams of horses for Thomas Cundle who was then felling trees and hauling timber widely throughout the region.

The senior Weaymouth progressed to Cundles’ foreman and had a hand in the opening of Dunlop Street West, then called Elizabeth Street, from Ferndale Drive to Parkside Drive. Later, he got involved in the droving of cattle from Simcoe County to Toronto, an arduous two-day journey each way. Later still, John Weaymouth Sr. operated a successful stage coach service, followed by a livery business located just east of the Clarkson Hotel, and finally a soft drinks enterprise which he gave up to take the position of bailiff.

In 1863, John Weaymouth Sr. married Janet Rankin Watson, the daughter of Scottish immigrants living in Oro Township. In time, four sons arrived: Samuel, Fontinore, John Rankin, and Ralph. Elizabeth was their only daughter.

John Rankin Weaymouth worked for a number of years in his father’s places of business before taking the job of turnkey at the jailhouse.

The turnkey’s job, although a position of some power, trust and respect, usually turned out to be more trouble than the paycheque was worth. For less than a dollar a day, J.J. Stevens, who held the job from 1877, was expected to dish out food, supervise work crews, clean cells and chase the prisoners who escaped custody with some regularity.

Stevens was forced to resign in 1880 after a very public battle with the jailhouse governor, Mr. Lang, during which he accused his superior of misappropriating funds and covering for the jail matron who had reportedly been in a relationship with an inmate, and who was later charged with larceny herself.

Stevens’ undoing was his own admission that he had been drunk at work on several occasions.

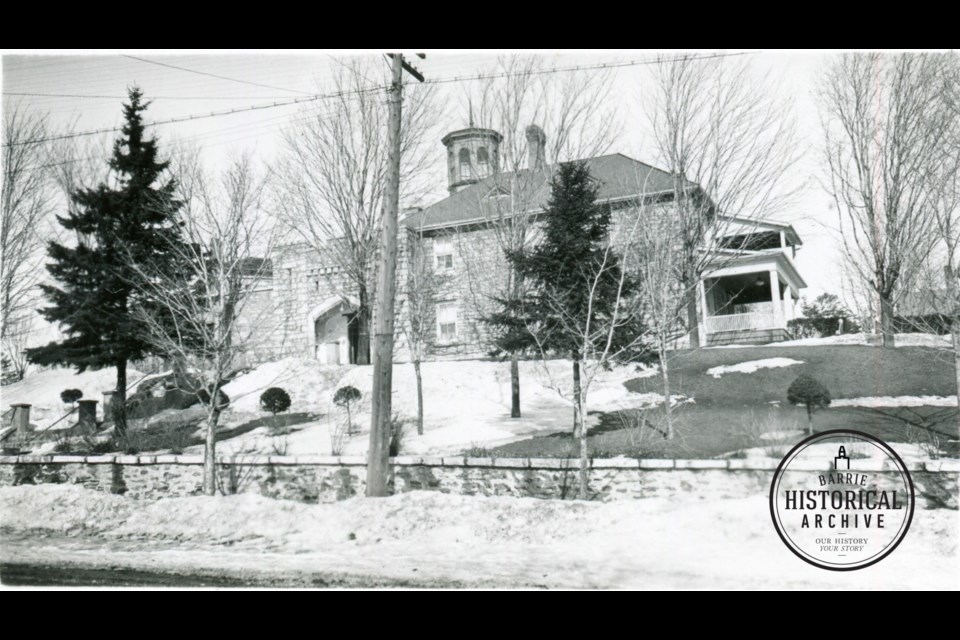

Turnkey R. Jennett stayed two years. Next came Thomas Caldwell, who could easily have written a book about his time in the stone fortress on the Mulcaster Street hill.

On numerous occasions during his 25 years on the job, Caldwell had been attacked by prisoners who had used discarded chair legs, picket fencing or a concealed club to beat the man. Once, his revolver was stolen as a prisoner jumped the exterior wall and, on another eventful day, that same firearm was used to shoot an inmate in the leg to fend off an attack inside the close quarters of a cell.

Weaymouth’s predecessor, William J. Reid, held the turnkey position from 1909. He succeeded C.G. Strange and Joseph Somerville who had filled the role on a temporary basis after Thomas Caldwell’s departure.

Mr. Reid, after 18 months on the job, found himself at the centre of a scandal. Even though Reid had left for his holidays on an early morning train, he was implicated in the escape of prisoner Percy Pelch on an August afternoon in 1911. Reid was accused of supplying Pelch with access to his street clothes, which allowed him to travel unseen in the community after he hopped the north wall.

Reid had to return to Barrie to address the rumours, which were found to be false and resulted in Pelch being slapped with the further charge of perjury. Nevertheless, the customary annual request for a raise of pay for the turnkey position was denied by council that year. By 1913, William Reid had had enough.

John R. Weaymouth worked under several jail governors over the years. In 1924, J.J.D. Banting became the head of the jail. His initiation was the embarrassing escape of 16-year-old Clifford French who had been left alone in the jail yard as Banting and Weaymouth oversaw the storing of the winter coal supply by the other prisoners.

Young French had used some old horseshoes, left over from inmate recreation time, to carve holes into the stone walls and make a ladder of sorts. If Banting and Weaymouth thought the French affair was their worst day at work, the events of 1931 would eclipse it by far.

Each week, the Barrie Historical Archive provides BarrieToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past. This unique column features photos and stories from years gone by and is sure to appeal to the historian in each of us.