Accidental poisonings were once very common.

One hundred years ago and more, hardware shops, drug stores and dry goods mercantiles could freely sell chemicals for the dispatching of rodents and garden pests virtually unrestricted.

Householders often stored pesticides and medications haphazardly together in kitchen cupboards and, in many cases, the vessels which contained the potions looked alarmingly similar.

What was not so easy to mistake was Paris Green. The popular paint tint, made by mixing copper verdigris with vinegar and arsenic, was a shocking emerald green.

Before it became common for pest control, Paris Green had enjoyed favour for many years as a food colouring, fabric dye, in wallpaper ink, in the manufacture of artificial foliage and in soaps.

Then people began to die.

Ingesting Paris Green or constant skin contact was often deadly, but it wasn’t realized until later decades that the vapour emitted from wet or mouldy tint infused wall coverings was also highly toxic.

Paris Green next gained the unfortunate reputation as being the poison of choice for people seeking to end their own lives.

On Monday, July 25, 1904, an inquest was held into the sudden death of well-known Barrie citizen, James Keenan.

The 62-year-old Irishman had lived for most of his life in this community and been employed at Sewrey’s Foundry for 21 of those years.

James Keenan had also been engineer during the early days of Barrie’s fire department and, up until the time of his death, he had been superintendent of the town waterworks.

It was at the waterworks, near the beginning of that year, that Mr. Keenan received a minor injury to his hand.

In this small town, everything was newsworthy and the local papers kept James Keenan’s friends and neighbours apprised of his condition.

“Mr. James Keenan is recovering from a very serious attack of blood poisoning” — Northern Advance, Jan. 21, 1904

“Mr. James Keenan is improving although he took a turn for the worse earlier this week” — Northern Advance, Jan. 28, 1904

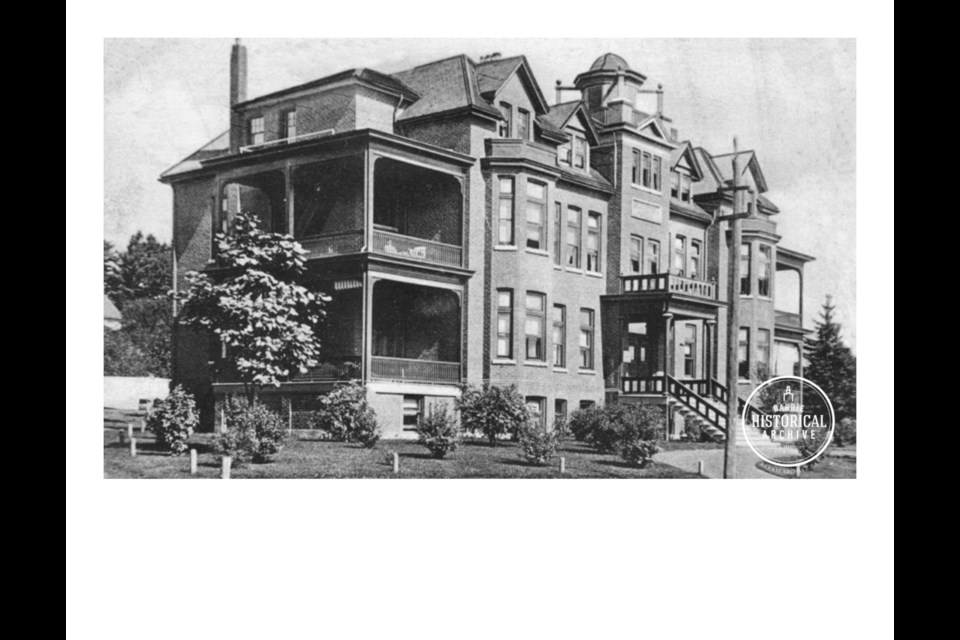

During the second week of February, Mr. Keenan was admitted to Royal Victoria Hospital in very bad shape. These were the days before the advent of antibiotics and options were limited for saving the life of a person in Keenan’s position.

“Mr. James Keenan’s condition has been steadily improving since the removal of his left hand. Amputation was performed just above the wrist” — Northern Advance, Feb. 18, 1904

At the inquest that followed his death, Keenan’s sons testified that their father had been quite depressed about the loss of his hand and that he had worried a great deal about how he would carry on working.

James Keenan had always been an active man. Just prior to his death, Keenan had submitted his resignation to the commissioners of the waterworks, but they had refused to accept it.

The eventual verdict read: “We find that James Keenan came to his death on July 21 from taking a dose of Paris Green, which resulted in his death about 12 hours afterwards. The jury further agree that no evidence has been received to attach any blame to any person or persons and that he came to his death by the wilful act of his own hand.”

The mental suffering of a desperate person was not well understood in those days and it can be argued that society still has a way to go to fathom that final act of complete desolation.

In a time when suicide was often seen as a selfish or sinful act, James Keenan was beautifully eulogized at his gravesite at Barrie Union Cemetery by Robert Algie.

“Some of us may feel a tinge of scorn and censure for the rash act that brought about the untimely end of he who sleeps here, and yet why should we? The tangled web of wish and will and want; the woven wonder of a life has never yet been ravelled back to simple threads. We do not know, we could not feel the pressure, the worries, the anxieties that forced themselves up on this strong but sensitive nature, and surely we will become more charitable.”

Each week, the Barrie Historical Archive provides BarrieToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past. This unique column features photos and stories from years gone by and is sure to appeal to the historian in each of us.