“Arrest Jas. H. Speers. Speers, about five feet five inches height, 35 years of age, light side-whiskers and mustache, dark complexion, has a sickly or delicate looking appearance, bow-legged and has a swinging gait while walking, inclined to stoop a little. When last seen was wearing dark grey clothes and a rowdy hat.”

If you think today’s grainy video stills of convenience store robbers are awful, the above notice, published in the Northern Advance in November 1878 is certainly something else to ponder.

James Speers was a wanted man. Chief Constable Joseph Rogers was quite interested in apprehending the “heretofore respectable Essa wagon maker” who had been accused of being behind a string of local frauds and forgeries.

Businesses belonging to C.H. Ross, J. Henderson, S. Bray, and W. Holt, as well as the Bank of Commerce, were collectively out some $3,000, current value nearly $78,000. They, too, were very keen on seeing the absent Mr. Speers reappear in town, preferably escorted by some lawmen.

How common was this sort of crime in old Barrie? More common than you might think.

In these small-town days, when everybody seemed to know their neighbours, businesses, in particular, were vulnerable to this type of offence. They were reluctant to turn down any sort of sales opportunities even if it meant a delay in payment. Promissory notes were certainly a risk but a gentleman’s word was his bond until proven otherwise.

The promissory note is something akin to a cheque, but instead of being a one-time payment from an individual, it can be extended or paid in installments and could be co-signed by another person as an assurance. Very handy for a person with no bank account – nor money!

What Mr. Speers was accused of was, for Barrie, a rather elaborately crafted swindle. Over a period of two years, storekeeper C.H. Ross began to get suspicious of Speers who only occasionally made small payments.

Ross eventually wrote to the main co-signers, a Mr. Bell and a Mr. Summerville, both well established Essa Township farmers. Replies affirming Speers’ stellar credit came swiftly back. In identical handwriting. On two halves of the same piece of notepaper.

Seemingly, Speers had been thinking ahead and intercepted the letters before they reached their intended destinations. Ross contacted the sheriff.

Mr. Ross and a police constable took a horse and buggy ride out to Ivy one afternoon and called in at the Speers home where they were met by the suspected man’s wife. Mrs. Speers was apologetic – her husband was away at Mono Centre that day. As the two men travelled to Mono, James Speers hopped onto a train heading to Hamilton and vanished.

When, two days later, Speers still hadn’t turned up, notices were sent to every chief of police between Barrie and the bridge to the United States.

The mystery, so far, ends here. Did James Speers leave the country and change his name, or was he sheltered nearby by friends and family? No report of a capture or trial has turned up in any of the local newspapers, none that I have found, but I have no doubt that some readers will be able to add to this tale.

The 1881 census for the community of Ivy appears to show James Speers’ wife, Margaret, living at the home of her parents and with her, are her two small daughters. James was evidently still keeping a low profile at that time.

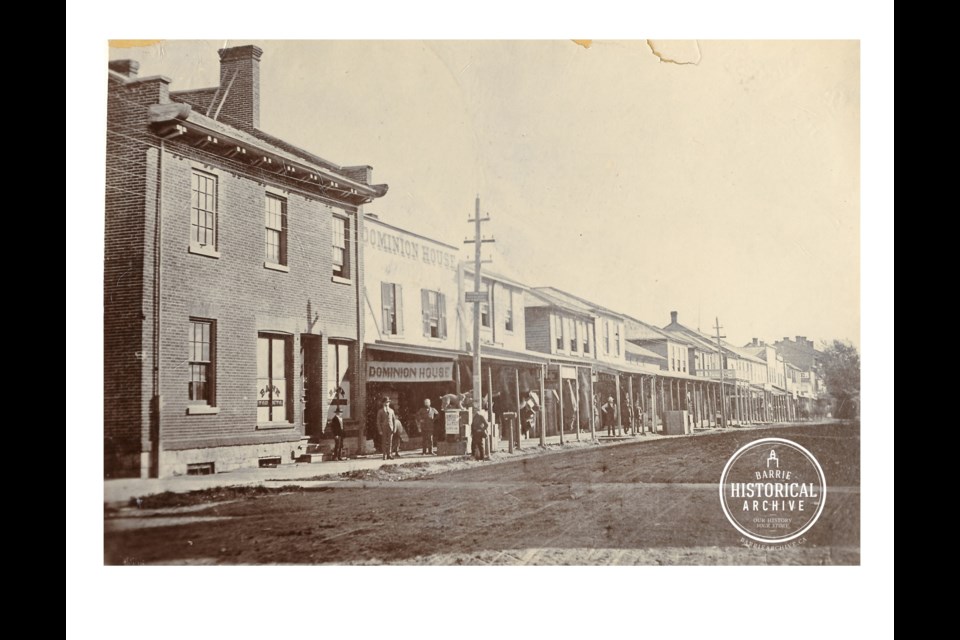

Each week, the Barrie Historical Archive provides BarrieToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past. This unique column features photos and stories from years gone by and is sure to appeal to the historian in each of us.