I spent most of Remembrance Day reading letters from the front. These were messages from Barrie lads, soldiers in the Great War, sent home to friends and family and sometimes shared in the local newspapers. Their writings were at times jovial, often dark, but always very descriptive.

What I was really after was tales of the Somme. I have been to the Somme region in northern France, and seen the now lush green fields where my great uncle, James Fletcher, fought and died in November of 1916. I was interested in finding the stories any Barrie boys who may have marched alongside Jimmy in those cold and wet days.

After reading one letter in particular, published Dec. 6, 1916 in the Barrie Examiner, I found myself sidetracked.

“Dear Dr. Barber: - Your very welcome letter to hand this morning, and I am trying to the best of my ability to send you a few lines by return mail. You must excuse my writing as I have not the use of my right hand. I got a piece of shrapnel through the upper part of my right arm.”

This was the beginning of a note to Dr. W. C. Barber from Private John Oakes who was recuperating in Coombe Lodge Hospital in Brentwood, England. The letter was dated Nov. 12, 1916, four days before my uncle would die, along with 20,000 other men, in the Battle of Ancre at the Somme.

Likely John had written to his mother in Burlington too, but lying in a hospital bed with nothing but time, he wrote to his employer, Dr. Barber, as well. He also mentioned briefly seeing a co-worker, Sid Fawcett, when his unit passed through Ypres earlier. They had all worked together in a seemingly friendly environment, at Simcoe Hall.

My question was what and where was Simcoe Hall?

With a bit of digging, and some assistance from the ever-helpful local experts, I learned about a place that I never knew existed. Although the name Simcoe Hall had only a brief tenure in Barrie, the building itself had a long and useful life both before and afterward.

You can’t spend much time in Allandale without seeing the name Burton somewhere, and there is a good reason for that. Three enterprising Burton brothers, Martin, George and James, all left their mark on this area. They came from Durham County about 1860, with Martin and George arriving first, and did well for themselves as lumber men. Trees fell everywhere from Magnetawan to Michigan under the Burton name.

A family tragedy brought James to town. One late afternoon, in June 1869, George Burton was tending a raft of logs near Hawkstone, when he decided to call it a day and take a canoe to shore. One of Lake Simcoe’s notoriously sudden storms popped up and upset his canoe. George Burton was drowned trying to swim to shore, and so James decided to move to Barrie to assist his remaining brother in business.

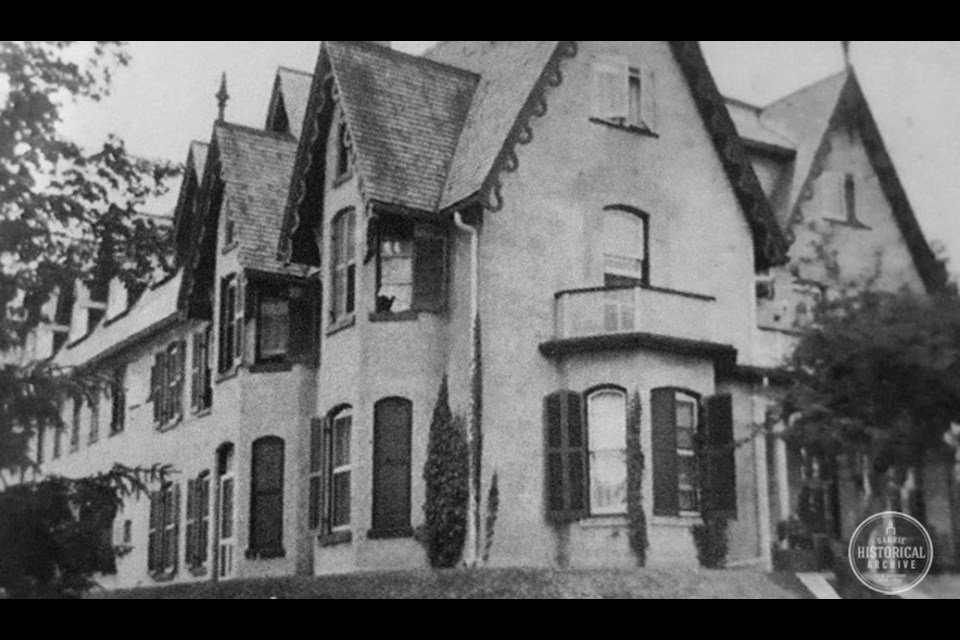

James and Martin Burton soon became lumber barons. The wealthy gentlemen were not long single, and in 1875 James married, with Martin following him to the alter in 1876. The two newly minted families lived under one roof, and quite a roof it was! Immediately, James had a fabulous brick house built for all of them where William Street meets Baldwin Lane.

Springbank, as it was called, was built on a large piece of property that was a bit marshy and had nothing much to offer other than a magnificent view of the lake, with Barrie across the bay. In 20 years time, the property was a showpiece, the finest in Allandale.

The Burtons did all the work on the grounds themselves. Mrs. James Burton planted the trees by hand and assisted in creating the lawns and terraces around the house. The fresh water spring that had once made the place so swampy, and inspired its name, was turned into a trout pond with a functional waterwheel that powered the distribution of water all over the grounds.

In 1910, James Burton passed away. By this time, Martin and family had moved into the former Robinson house at 105 Toronto St., so James’ widow moved to Toronto to be with her own family.

Springbank, now unoccupied, caught the attention of the earlier mentioned Dr. Barber, of Kingston, Ont., who had a vision of opening a private sanitarium somewhere in the province. Renovations and additions were begun in 1911 and the doors opened to great fanfare in 1912.

The home was aimed at wealthy ‘neurasthanics’, folks with assorted nervous disorders, plus sufferers of gout, rheumatism and digestive disorders. These exclusive clients could convalesce in sumptuous style and take advantage of various hydriatic baths, electric massages and light cabinets, then return to their rooms nattily fitted out by the T. Eaton Company.

It is here that we meet John Oakes. When John enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in September of 1915, he listed his profession as florist, and he was indeed employed as a gardener at Simcoe Hall. John had been on staff since nearly opening day, but when he lost a brother, Albert, in France, he was compelled to join up. Albert Oakes was killed in action near Langemarck in Belgium and has no known grave. His name, along with 34,984 others, is inscribed in the Menin Gate, the memorial to the men who fought near Ypres and were never seen again.

Sidney Fawcett was the well-liked book keeper at Simcoe Hall. As a sergeant with the 35th Simcoe Foresters, he was one of the first to enlist when war broke out in Europe. At his November departure, he was given a going-away party at Simcoe Hall and presented with a gold watch, a gift from the patients and attendants at the sanitarium.

As far as I can tell, both John Oakes and Sydney Fawcett made it through the war. John might have come to appreciate his hand wound, the ‘blighty’, that perhaps saved him from the Hell of the final Somme offensive that took so many lives.

The Burtons too were touched by this horrific war. James Burton’s only son, Franklin Lindsay Burton, was a career military man and he naturally enlisted. Lt. Col. Burton signed on with the 216 Battalion in Toronto on Feb. 17, 1916. He was 40 years old. Six weeks later, his 19-year-old son, James Lindsay Burton, also signed with the 216th. The father came home. The son did not.

Meanwhile, Simcoe Hall carried on seeing well-heeled patients until the 1930s. Perhaps the poor economic situation spoiled the venture, but the Town of Barrie was forced to eventually take the building over for unpaid taxes.

The fine old Burton mansion wasn’t done yet. The town was very happy in 1940 when the Grand Lodge of Ontario, IOOF, offered to lease the building for at least the duration of the Second World War. Rent was agreed upon as $1 a year, and no taxes to be paid. Also available was the option to purchase the property for $10,000.

It would appear that a purchase was eventually made as the IOOF has remained and vastly expanded on the site. The former Burton home is gone, torn down over twenty years ago, having sheltered both rich and poor for more than a century. You could say that she ‘did her bit’.

Each week, the Barrie Historical Archive provides BarrieToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past. This unique column features photos and stories from years gone by and is sure to appeal to the historian in each of us.