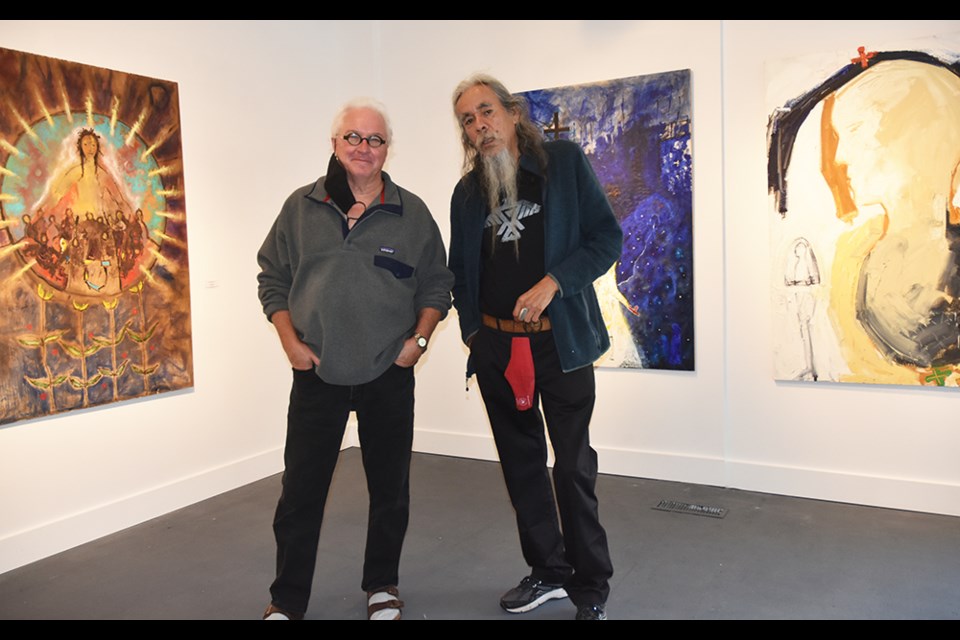

Artists Ted Fullerton and Paul Shilling first met back in the early 1990s when Shilling was on the healing journey that would lead him to recover his culture, his spirit and his Indigenous name – Dazaunggee, Sky Buffalo.

Born into the Chippewas of Rama First Nation, he wasn’t part of the Sixties Scoop that snatched First Nations children from their families and “integrated” them into white culture. As the youngest of 13 children, he was not sent to residential school, like his parents and several of his siblings.

“I wasn’t scooped away, but I was in Rama School, and we were forbidden to speak our language,” Dazaunggee says.

All the same, he was impacted by the ripple effects of those policies – cruelty, poverty, violence – experiencing more anguish before the age of seven than most people experience in a lifetime.

The two artists, born in the same year and same month but into very different backgrounds, immediately connected with mutual respect for each other.

Their paths diverged and they didn’t meet again until the spring of 2018 when, in a day-long conversation they renewed the connection, this time through the lens of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the residential schools.

“We had a conversation about truth, about reconciliation, about shame,” says Fullerton. The result was a decision to continue the conversation not in words, but “through artwork, in images.”

They each did a painting, sight unseen, and sent it to the other and then painted a response.

The two pairs of paintings became a Dialogue in Image: Dazaunggee to Ted – Ted to Dazaunggee, that now form the basis of the new exhibition in the Main Gallery at be contemporary art gallery in Stroud. Together in Spirit-Dialogue in Image also includes several newer works that carry the conversation between the artists beyond the initial exchange.

The exhibition is described in the artists’ statement as “an honest and perhaps controversial point of encounter to the current topics of original people, colonization, spirituality, aesthetic sensibilities, expropriation of Indigenous land, culture, language, identity, shame, art and stories… an ongoing exploration and declaration for reconciliation and understanding.”

Everything has meaning in the exchange, from the choice of symbols to the colours used in each painting, the artists explain.

“All of them are very loaded with symbolic references. I am very interested in iconography,” Fullerton says. “That’s the way I engage with the world.”

Challenged to address the residential schools and the impact of Christianity, his most recent works include ‘Criss Cross at the Crossroads with Indian Red,’ centring on a cross painted in the “difficult” colour of ‘Indian Red,’ and ‘I can see Clearly Now,’ his first painting of 2020, done on Jan. 1.

In the latter, two snakes cover the eyes of a white figure. The snakes are doubly symbolic, not only of the meaning in traditional Christian mythology, but also the deeper and older meanings of renewal and rebirth.

“The serpent within Judeo-Christian theology takes on the symbolic inference of deceit and the fall of man. Yet within other cultural considerations it is emblematic of healing, fertility, life and the Axis Mundi, that point of truth and understanding that words are unable to express.”

Fullerton uses red to express love and affection, but also deceit, anger, aggression; black and white for positive and negative, but also to represent the evolution from darkness to light; dark blue for knowledge.

Colour symbolism is also part of Dazaunggee’s work.

In his first painting, a path descends from a cross, through a dark landscape of midnight blue, representing the Sky World. In the foreground are two figures – an Indigenous man, sketched in black, holding a bottle, linked with a luminous being, painted in white, who holds a pipe filled with sacred tobacco. Both represent the artist.

The cross is an important element in many of Dazaunggee’s works.

“This is the source of my suffering… ugly experiences,” he says.

The cross, for him, “has nothing to do with Jesus and nothing to do with God,” but everything to do with power, colonial oppression and cruelty.

For years, he says, “the bottle was my saviour. Then I realized that the spirit was always with me.”

It was his older brother, Arthur Shilling, who introduced him to the power of creativity, but Dazaunggee only began painting in 1980.

“Before that, I was not in touch with my spirit.” Now he uses his “visions, feelings” to create his emotionally-charged artwork. “My spirit becomes clear, and it shows me.”

The colonial church, especially the Catholic church, is still a symbol of darkness for Dazaunggee, encompassing the crushing of Indigenous culture, and the abuse of children in residential schools.

“They stole the children,” he says. “Before that, we were connected to truth, to everything” - linked with the earth, hunting and fishing for food, relying on the wisdom of elders for healing and understanding. It’s all been replaced. We’ve been forced to trade spirituality for Christianity.”

As he once said in an earlier conversation with Fullerton, “The old teachings are not there any more to tell us how extraordinary we are.”

Dazaunggee’s paintings are a rediscovery of that spirituality through the development of personal understanding and acceptance of all life experiences, positive and negative.

“I wanted to express what I was feeling, as I was healing. Say something in the world… To heal is probably the most frightening thing you can do. You take ownership of your feelings.”

From the start, Dazaunggee decided, “I’ve got to speak about what’s happening, what we have to do to unravel the dogma,” shining a light on all that transpired and has been “covered up with shameful blankets.”

However hard the experience, “I reach inside and pull out the wisdom. The spirit doesn’t ‘believe’ – it knows,” he says.

In poetry, he writes: “This is my life – I have only one shot at it/To paint, to write is my voice/My way of healing/ To uncover my child, my spirit.”

And in a recorded exchange for the Art Gallery of Mississauga’s show ‘Darkness does not belong in Shadows’, Dazaunggee says, “It’s about being a human being. It’s about a beautiful journey. We all need to understand that.”

Reconciliation is not a matter of blaming others, of hatred. “Reconciliation is the work I need to do for myself,” he said.

Together in Spirit – Dialogue in Image expresses “that raw conversation, bringing it forward through art,” says Fullerton, noting that if the relationship between Indigenous people and Canada is to heal, there must be acknowledgement and ownership of the past.

“There can only be reconciliation when we finally walk together and move out of our mutual safe ignorance to find, hear and speak truth. We can no longer say, ‘We didn’t know.’”

Fullerton admits that before he began his conversations with Dazaunggee, he was unaware of the full impact of colonialism, or the details of Canada’s Sixties Scoop, which saw an estimated 20,000 Indigenous children taken from their families, to be adopted by white Canadians.

“The shame I felt, in not even knowing that ... he opened my eyes to something I was not even aware of.”

The exhibition offers an exploration of painful truths, but also an awakening to spiritual beauty through its powerful images, and a call to action.

As Fullerton notes, “Everyone has it within to speak that, as truth.”

"To reconcile is to understand yourself," says Dazaunggee.

There is a different vision of experience in Fruits of the Garden, a show of recent works by Sadko Hadzihasanovic, in the smaller BHCV Project Gallery.

Hadzihasanovic escaped the Serbian conflict of the 1990s, coming to Canada with his wife. For years, much of his artwork juxtaposed images of children and guns, expressing a loss of innocence and the inheritance of hatred that result from war.

His newest works, completed during the pandemic, are in essence a return to “the garden,” to a more idyllic world of family and nature although even the brightest gardens harbour modern temptations of alcohol and cellphones, providing a link to the outside world.

During the pandemic, “our lives shifted in unpredictable ways. We had to re-imagine who we are as society and who we are in our personal lives. Being overwhelmed became our constant. In a search for some place, most people started going to nature, seeking refuge from everyday brutality of bad news,” he writes.

“I too was able to reconnect with what nature offers us, and to re-establish my place in it.”

His paintings capture a return to the garden, to simple pleasures and nature – although works like Sunday in Oakville Garden are deliberately unfinished, suggesting an evolution that is ongoing.

Together in Spirit-Dialogue in Image and Fruits of the Garden both continue at be contemporary art gallery, from Oct. 9 to Nov. 6.

The gallery, located at 7869 Yonge St. in Stroud, is open Wednesday to Saturday, noon to 5 p.m. Due to pandemic protocols, the number of visitors permitted at any one time is limited to five. Masks and social distancing are required.

Come in and browse, or book a viewing at [email protected] or 705-431-4044.

There was no opening reception for the shows, but a closing reception is planned for Nov. 6, from 1-4 p.m. Gallery curator Jeanette Luchese is also hoping to organize an artists’ talk – a verbal dialogue, between Ted Fullerton and Dazaunggee, to be shared with the public.

For more information, click here. The shows have been sponsored by Strachan/Moore SOLUTIONS ink.