With the opioid epidemic showing little signs of letting up, what do emergency services workers encounter on a daily basis in the Barrie area?

The rate of opioid-related deaths in January, February and March of this year shows Simcoe-Muskoka above the provincial average, and among the worst regions in Ontario, behind only Toronto, Peel Region and Hamilton, according to the latest data from the Office of the Chief Coroner.

According to preliminary data from the Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit, there were 33 confirmed and probable opioid-related deaths in the region in the first three months of 2022.

As dire as the information is, many first-responders say those numbers don't tell the whole story.

Barrie police Const. Jamie Westcott, who is with the department's community safety and well-being team, sat down with BarrieToday to discuss what officers can see on day-to-day.

Westcott said they average two to three calls daily and consider that just the beginning.

“It's like an iceberg, right? If we’re getting two to three calls a day, that's what is being reported or detected. The bottom part is what is not being reported, so you can imagine what is going on without our knowing,” Westcott said.

Westcott says the number of opioid-related calls per day fluctuates and can change on weekends as well as paydays.

“I deal with social disorder and so when I deal with people, I can tell whether they just got paid. There is a difference,” he said. “Certain things occur with them during that first week of coming into money — paydays are a huge difference maker.”

Westcott and other local officers carry Naloxone (Narcan), a nasal spray which reverses the effects of an opioid overdose, with them at all times. The officers can sometimes encounter what he called “combativeness” from someone who has been brought back from the dead.

“Fentanyl will slow down your respiratory system, so we have to look for signs. We check the pulse, the breathing and, if needed, we will shoot the Narcan up the nose and into the bloodstream,” Westcott said. “An issue is when someone is woken up from that, they instantly go into withdrawal, what is sometimes called dope sick.

"We see people not wanting to go to hospital and get fixed up because they need that high. They don’t want to lose it or if they do because of the Narcan shot, they get mad," he added.

Westcott said community partners who deal with the city's drug issue first-hand are pushing for harm reduction, much like methadone was used in place of heroin, to keep people from crashing into withdrawal and keep them safe.

As far as first-responders keeping safe on calls, he says there are different strategies and everyone has a different approach.

“Personally, when I go to a call, I have to protect myself and not be a sponge, taking on all that trauma. It is really sad when you get to a call and someone has passed or they have just been revived. But you have to switch gears and do the job," Westcott said. "That human element kicks in, though, and I often sit back and wonder where it all went wrong for this person and the countless others dealing with this addiction.”

In the 25 months of available data since the start of the pandemic — from March 2020 to March 2022 — there have been 323 opioid-related deaths in Simcoe-Muskoka. This is more than 75 per cent higher than the 182 opioid-related deaths in the 25 months prior to the start of the pandemic — from February 2018 to February 2020.

Sarah Mills, who is acting deputy chief for the County of Simcoe Paramedic Services, says approximately 80 per cent of the calls over the year receive Naloxone assistance.

“There isn’t really a spiking point. It seems to have been a gradual and steady climb in calls,” she said.

Mills has been in the paramedic field for 20 years and while she's no longer on the front line, she hears from her co-workers that it's a challenge.

“They’re very complex calls with a lot of unknowns. The scenes and people can be unknown and that makes it difficult to say the least,” she said. “Our staff have a lot of training to help with that and are able to implement that training day-to-day.”

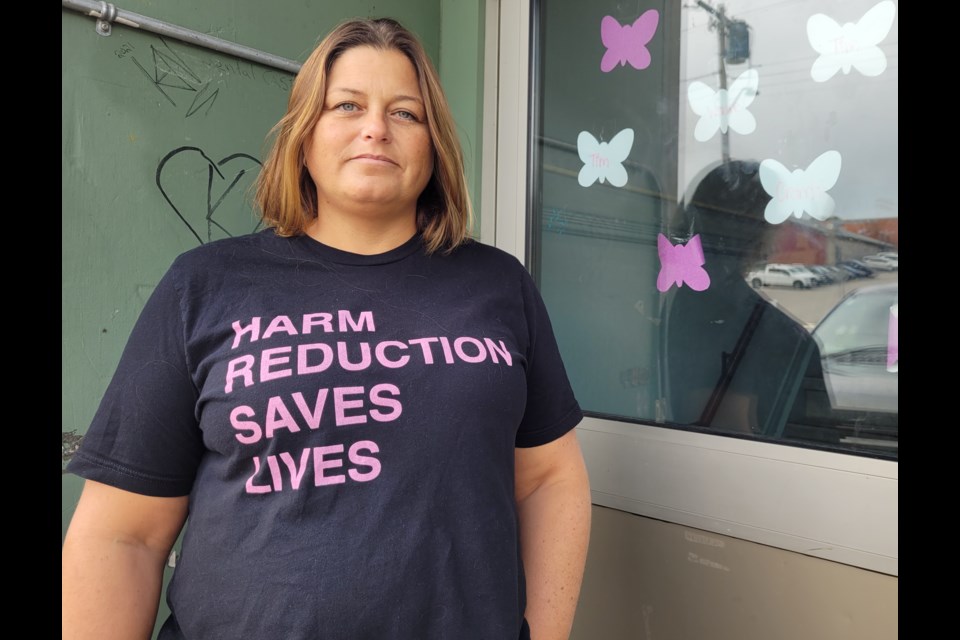

For the past two years or so, the David Busby Centre — which is a not-for-profit organization that helps people experiencing homelessness, and sometimes drug addiction — has used the image of a butterfly to signify someone dying in the community they serve. When an overdose or toxic-drug death is experienced by the organization and those who use their services, the Busby posts a butterfly on its social media channels, on the walls or in their windows.

Busby Centre executive director Sara Peddle told BarrieToday there have been too many butterflies this year, with about 75 lives lost so far.

“It's honestly so hard to keep track because it is happening too often,” Peddle said. “We’re fortunate that our team and teams in other community partners are trained to reverse overdose because we are coming across it so much. Otherwise, we’d lose a lot more people.”

Peddle stressed this is not a Barrie problem, as it is happening everywhere and the prejudice around it is affecting all people dealing with addiction.

“It is unfortunate because some look at it as the person’s fault, the fault of the person who is struggling with the addiction, but it really isn’t,” she said. “There are so many things from a policy issue, a health-care issue, a housing issue and, in the end, it is a human issue. We absolutely have to treat people with dignity and compassion.”

Barrie Fire Chief Cory Mainprize says he has seen the crisis become heightened since about 2016. The fire department now responds to opioid overdose calls “almost on a daily basis,” he added.

“The numbers continue to remain very high and a lot of them seem to be focused in the downtown area, but we are seeing more and more outside that part of the city,” Mainprize told BarrieToday.

While some may view the overdose issue as a problem for those experiencing homelessness, Mainprize says that isn’t the case.

“The opioid epidemic is not isolated to the homeless or vulnerable population. We do see overdoses in all different socio-economic groups and it certainly doesn’t discriminate,” the fire chief said.

A supervised consumption site (SCS) has been proposed for 11 Innisfil St., directly behind Barrie Fire headquarters. The Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit and the Canadian Mental Health Association Simcoe County Branch are the lead agencies behind the local application.

An SCS provides a safe space and sterile equipment for individuals to use pre-obtained drugs under the supervision of health-care staff. Consumption means taking opioids and other drugs by injection, smoking, snorting or orally.

The facility has Health Canada approval, but still awaits provincial approval and funding.

City council endorsed the site in June 2021, and Health Canada recently okayed a Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) exemption, which would allow SCS staff at the facility the ability to test and handle drugs without any criminal sanctions.

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)