Deep within our local valleys and wet areas may be found growing a variety of conifer trees: white cedar, balsam fir, eastern hemlock, black spruce and tamarack. Although they share the same habitat, each has its own story of how it arrived here and in what manners it has provided to the well-being of the surrounding neighbourhood.

The eastern hemlock is a favourite of mine, as it seems the more I learn about them, the more is revealed as to how we might live a good life. Yeah, I know, sounds heady, but really, these trees can handle a lot and deserve our respect.

Their natural role (as with all trees) is to suck in air, extract carbon dioxide for internal growth and exhale oxygen. Without plants doing this daily function, we’d all be dead by now. Actually, we would never have even got started. So, we already have a partnership with trees, as we do the opposite: inhale air, extract oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide. Lovely sharing arrangement.

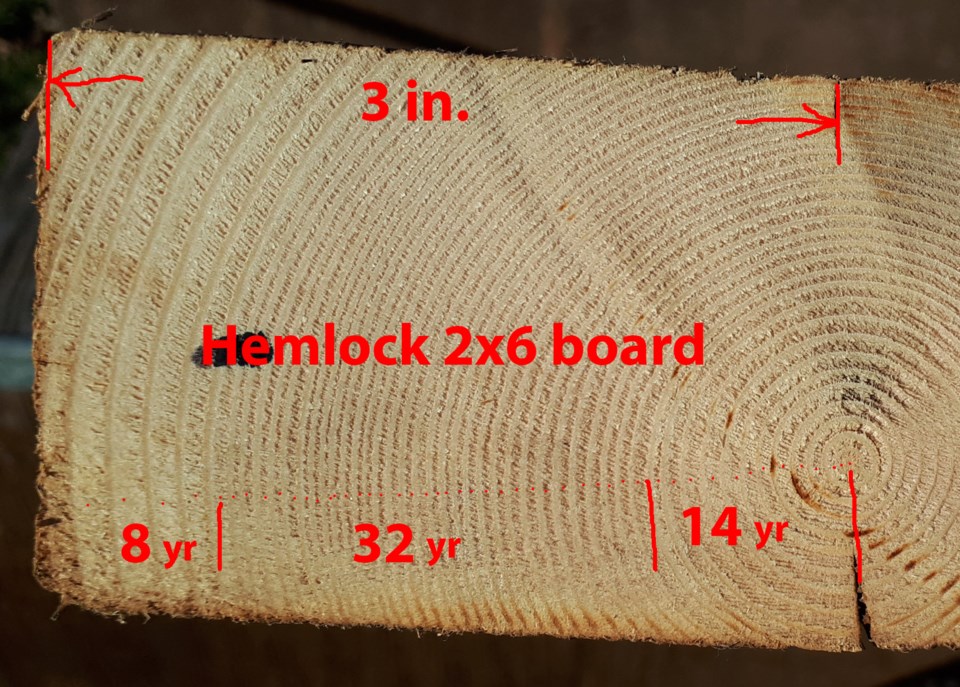

Hemlock also has the ability to show patience. Like humans, they grow vigorously in their youth, slow down when oppression surrounds them, kick-start their growth again when opportunity occurs, and then slow down in old age. Take a look at the attached photo of a hemlock 2x6 board and follow along:

Let’s say a couple of seeds fall on the forest floor — in this case, a damp forest floor — as one seed is from a hemlock cone and the other is from a yellow birch. Both germinate and set down roots into the cool, wet soil, and both grow with gusto for 14 years. But then the yellow birch takes the lead, growing a tad higher and develops wide-reaching branches with leaves that shade the forest floor.

While hemlock is no doubt miffed that his neighbour, the birch, is now hogging the sunlight, it continues to grow as it is shade tolerant. The annual growth rings tighten up as 32 years of summer growth is restricted due to the heavy shading. Patience is displayed, as well as quiet, determined growth.

In time, the yellow birch will die long before the hemlock, possibly from being storm tossed or from insect infestation or from the lumberman’s saw. (Ontario provided most of the yellow birch required in the Second World War to produce the veneer needed for manufacturing Mosquito bombers.)

With a sudden opening in the forest canopy, the hemlock takes full advantage of the increased sunlight and bursts forth with renewed vigour. For its last eight years of growth, as found in this board, rings are widened as carbon is brought in and cell growth is accelerated. The hemlock now takes on girth and height, becoming a recognized individual in the forest community.

It has taken this particular tree 54 years to achieve a six-inch diameter; when you come across a hemlock with a trunk diameter of a foot or more, it will have been growing there for at least a century.

With age comes the inevitable slowing of cell production. Trees don’t grow higher than capillary action can carry up moisture, and surrounding trees are in equal competition for sunlight and soil nutrients. And so there are smaller growth rings produced as the hemlock settles into a quiet existence (not seen in the photo as the 2x6 has been cut from the heart of the tree).

Another cool thing about hemlock is that the roots from one tree will intermingle and eventually merge with the roots of another tree. This allows for the sharing of soil nutrients and water, so if one tree happens to be on shallow soil and is in danger of drying out, the neighbouring hemlocks share what they have gleaned and the whole community prospers.

Many species of wild animals use the hemlock: Red squirrels and crossbills (a type of bird) eat the cones, deer and grouse eat the succulent growing tips, warblers seek out insects living in the rough texture of the bark, and man — well, man started by just using the needles soaked in warm water to make a great tea rich in vitamin C, and sometimes the thin, tough roots as stitching material for birch-bark vessels.

But as man is industrious and requires copious building materials, hemlock wood became in demand for structural framing of barns and early farmhouses. And it was also discovered that hemlock bark contains a lot of tannin, and tannin is infused to leather to make it strong and supple. Tanneries in Huntsville and Barrie created winter jobs for hundreds of settlers who went to the woods to remove the hemlock for lumber and a steady supply of bark.

So, in my example of a chunk of 2x6 lumber, we can see the story of one hemlock, from start to finish. After working up a good sweat by using this lumber, I can then take a cooling walk through the swamp from whence it came, pausing to catch my breath with a lung full of clean, oxygen-rich air, expelling some carbon dioxide to aid them in their growth. Taking a moment to appreciate the role of hemlocks in my life.