This week, the province announced a review of regional governments which has thrust the County of Simcoe structure into the spotlight.

County of Simcoe chief administrative officer Mark Aitken sat down recently with Village Media to talk about the history of Simcoe County, and how the separated cities of Barrie and Orillia fit in to that framework.

Aitken points out that this isn’t the first time the government has taken a closer look at geographical governance.

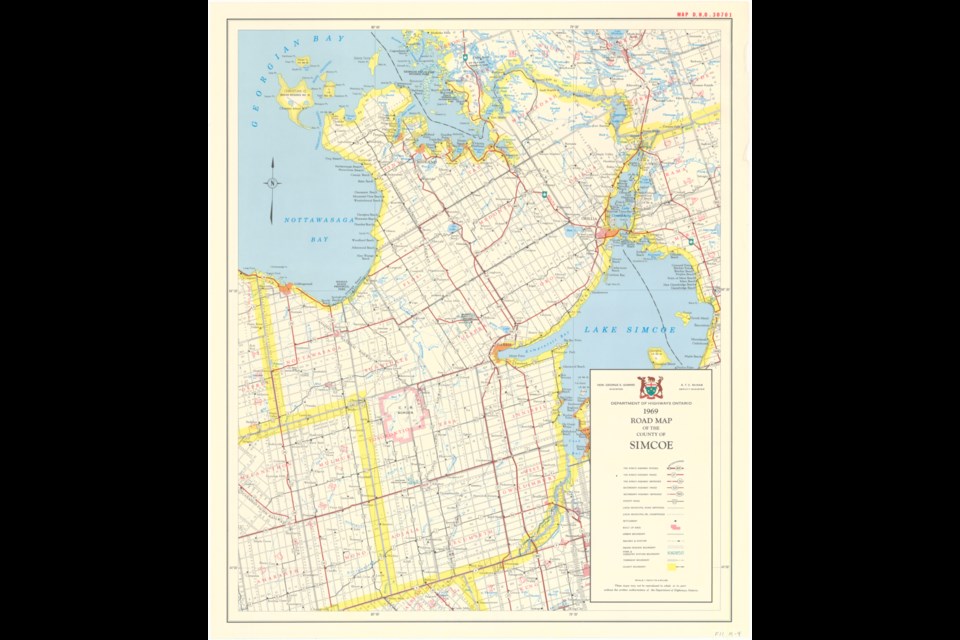

“In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a lot of discussions around the larger municipalities, generally around the GTA (Greater Toronto Area) that were struggling with growth, and how to better service the growth,” he said.

Aitken points to York, Peel, Durham and Niagara as being examples of areas that were affected, which are also, in addition to Simcoe County, areas that will be looked at under the new provincial review.

“So the Ontario government at the time made them regional governments and had them co-ordinate specific growth-related services,” he said.

“Back then, they gave the regions various powers under the Municipal Act that other upper-tier governments didn’t have," Aitken added. "Counties back then didn’t look after as many services as they do now.”

According to Aitken, originally there was a distinct difference between a region and a county, and while Simcoe County was considered to be added to the list of regions back in the 1970s, ultimately it was decided that Simcoe County didn’t have the same growth pressures and population the regions were experiencing.

“Back in the 1970s, I could argue that there was a distinct difference between a regional government and a county. Now, there is little or no difference. Things have changed a lot,” he said.

Since the 1970s, the County of Simcoe has taken on services such as paramedic and emergency services and social services, such as Ontario Works and housing.

“That’s 100 per cent consistent with regional governments,” said Aitken.

One major difference between counties and regions is that regions tend to take on water and wastewater services.

“There are certain counties that look after it as well, and certain regions that don’t look after it. The models are different. It’s a little confusing, but that’s the way it is,” said Aitken.

Even before the regional lines were drawn in the sand, the cities of Barrie and Orillia both saw the potential for their communities to grow. Barrie incorporated as a city in 1959, and Orillia followed suit a decade later in 1969, both establishing them as separated cities.

“Back in the 1950s and ’60s, the county existed, but didn’t provide services the way they do now. Some urban areas were growing at a certain rate and believed that they wanted some autonomy from the county as the upper-tier government,” said Aitken. “Back in the ’50s and ’60s, the provincial government had some allowances that urban areas of a certain size could opt out and become a separated city.”

Aitken says that at certain points in history, people have made a big deal over the pros and cons of a regional government versus a county government.

“How things might evolve in the future is up to the government of the day,” said Aitken. “We’ve got great partnerships with the cities of Barrie and Orillia.”

Budget numbers on everyone’s mind

The total proposed county budget for 2019 is $550 million.

Barrie and Orillia residents do not pay taxes at the county level. Instead, the municipalities allot a specific amount in their own budgets to pay for the use of some county services.

For the separated City of Barrie, their contribution comes with a price tag of $22.5 million for 2019, an increase of 9.5 per cent over 2018 numbers. For the separated City of Orillia, their contribution will come with a price tag of $5.6 million for 2019, an increase of 2.5 per cent.

“I’m sure there are residents in the City of Barrie (or Orillia) who might say, ‘Geez, that’s a lot of money,’ whereas, from time to time, I have to deal with county councillors who are arguing with me that maybe the City of Barrie and the City of Orillia aren’t paying their fair share,” Aitken said with a laugh.

“But, at the end of the day, I think everybody recognizes there are efficiencies. (Orillia) Mayor Steve Clarke and (Barrie) Mayor Jeff Lehman attend committees of the whole and they participate in discussions on the services and I think the relationships are great.

“As it stands right now, I think things are pretty positive.”

In 1959, Barrie decided to opt out

Barrie incorporated and became a separated city in 1959.

Mayor Lehman’s father, Bob Lehman, was a consultant whose company was contracted by the city in the 1990s to look into options around the possibility of restructuring the county. While the suggestions put forward never came to fruition, Lehman still feels a personal connection to the issue.

“There’s been different occasions over the 60 or so years that Barrie has been a separated city where there’s been discussions around possibly going back into the county or amalgamating with other municipalities. The big battle, of course, was annexation for many years with Innisfil,” Lehman said.

In 1959, Barrie was on the cusp of major growth.

“Urban areas were growing very quickly; they were where industry and commerce was located. There were also additional services that were needed in the cities that aren’t needed in rural areas.

“Back in 1959, the rural areas were still really rural,” said Lehman, adding that while Barrie and Orillia weren’t that different in terms of size at that time, a lot of manufacturing industries were in those areas in the post-war era. The economy was changing at that time, from mining, fishing and forestry into more industries that relied on manufacturing.

“I think a lot of the reason it was felt that cities needed to be separated was so they could control their own destiny because they were fundamentally different,” said Lehman. “Most of those reasons are still valid today.”

One of the benefits of being a separated city is not having to worry about the difficulty that can come with trying to co-ordinate efforts between two governments, Lehman said.

“When I look at some of our competitor cities such as Markham, Vaughan or Richmond Hill, they’re all in two-tier governments with York Region... you do inevitably get some difficulty in co-ordinating what’s going on between the two levels,” he said. “Sometimes, even conflict where an upper tier wants to go in one direction and the lower tier wants to go in a different direction.”

It’s also easier to co-ordinate needs within the city when most of the services are all under one roof, said Lehman.

“For example, when our police service needs to co-operate with bylaw (enforcement) and the roads department, it’s all one organization,” he said. “You don’t have different budgets and different councils to go to.

“We don’t face the challenge of, not having control of something that’s very valuable to our community. I think, on some level, it’s more efficient to have a single level of government.”

However, Lehman is quick to clarify that it doesn’t mean the city has ever had that problem with the County of Simcoe.

“Our partnership with the County of Simcoe has been very productive in the last 10 years,” he said, pointing to the Lake Simcoe Regional Airport, the LINX transit system and social housing as examples where collaborations between the upper and lower tier have been very positive.

“It just means that the government (in Barrie) is closer to the people and more accountable to that one community.”

Lehman also points to some of the negatives of being a separated city.

“We have to pay for everything ourselves,” he said with a laugh. “There are some situations in other regional systems, like Peel and York regions, where by virtue of the upper-tier authority being very large – York Region has two million residents and a capital budget of billions of dollars – there’s more of a capacity to take on big projects. There’s more fiscal capacity to shift money among services.”

The property tax bills overall tend to be higher in many two-tier systems, he said.

“If you look at separated cities across Ontario, what you’ll find is the fiscal challenges will be greater, because we just don’t have the capacity to have residents of (multiple) municipalities all chipping in to a budget,” said Lehman.

In regards to the 9.5 per cent increase from the County of Simcoe in this year’s budget, Lehman takes it in stride.

“It’s big,” Lehman said with a laugh. “About three or four years ago, the county realized that their capital budget requests of Barrie and Orillia, but particularly Barrie, were really going to grow. They were going to be a lot bigger because we had major social housing projects coming and the first responders campus was coming. Even though we’re paying for the police part of that, we also pay for one quarter of the paramedics part of it.”

“Just generally, there was a lot of capital coming down the pipe, so their request for Barrie was going to go up a lot.”

According to Lehman, the County of Simcoe worked hard with the City of Barrie to essentially work out a payment plan so they wouldn’t be asking for the money in one large sum all at once.

“That’s really helpful,” he said. “I can only say good things about the county leadership and what the last county council did.”

Lehman also clarifies that a lot of the increases this time around come from cuts the provincial government has made -- specifically to social housing -- downloading the responsibility of covering those necessary costs to the county and municipalities.

“The county basically said they’re going to try to make up for that so we don’t have to go without the repairs... that it was going to fund,” he said. “That also increased the ask of Barrie. It’s more of a problem with what the province did, more than what the county did.”

For our story on the Barrie request in the County of Simcoe 2019 budget, click here.

Ten years later, Orillia separated

In 1969, Orillia incorporated as a separated city.

“You have to go back historically. The counties were formed back in 1843. They were geographical governance areas back in those days,” said Orillia Mayor Steve Clarke. “They were trying to create kind of a governance model for Ontario.”

“We have a wonderful relationship (with the county) in a number of areas, like social housing, Ontario Works, paramedics... (but) there are other areas where we have become stewards of our own ship,” added Clarke.

Clarke points to the county just opening a new paramedic station on West Street in the heart of Orillia as an example of good collaboration.

“The response times were good before that, but they have dropped even further having that central location,” said Clarke.

Clarke also points to the Orillia Community Project on the former Orillia District Collegiate and Vocational Institute (ODCVI) property.

“We pay into a pool, and sometimes that pool will benefit other municipalities, but that pool comes around and benefits Orillia too,” he said.

The City of Orillia is the only municipality in Simcoe County that does not put money forward to the county for the maintenance of the Simcoe County Archives or the Simcoe County Museum.

“We have our wonderful museum of art and history, known at OMAH. They house all our historical artifacts and displays and account for our history in that way,” said Clarke.

“Anytime you’re talking about a partnership, it has to truly be a partnership. It can’t just benefit one side. We’re always trying to do what’s best for our citizens, and right now, I believe this relationship is what’s best for our citizens.”

Clarke said he appreciates the existing relationship between Orillia and the County of Simcoe.

“Over the years, when the county has taken on certain services it’s actually been a very good thing for economy of scale and providing services at a much better level. We don’t look at boundaries. The services are there for people.”

For our story on the Simcoe County 2019 budget request of the City of Orillia, click here.