Having lost her father to a violent killing, Kim Kneeshaw suddenly found herself navigating the foreign world of the legal system.

It was the 1990s and the staid Barrie courthouse — with its rules and formalities and a rabbit’s warren of after-thought adaptations and additions and hard wooden benches — was all a bit overwhelming. With no access to any particular services, she relied upon the kindness of an officer who doubled as a sort of victim liaison.

At one point, as she was preparing to testify at the preliminary hearing, the Orillia woman fell ill and, with no other other options, found herself lying on the couch in the Crown attorneys’ office.

“There is no place to go,” Kneeshaw remembers in an interview with BarrieToday. “The lack of accommodation made for victims is horrific. The whole thing was so re-victimizing.”

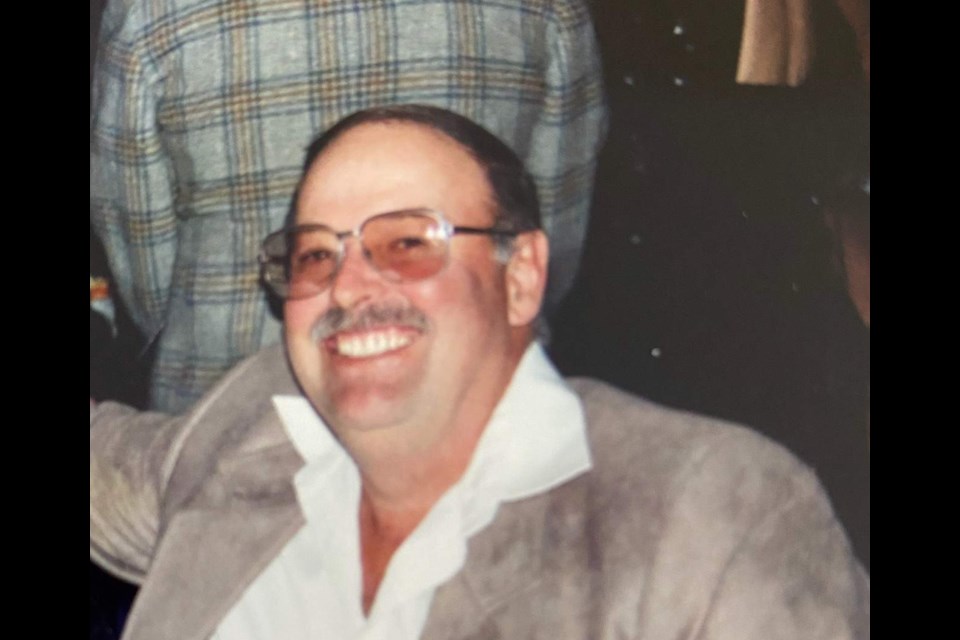

Her dad, 51-year-old Paul Kneeshaw, was gunned down on his rural property north of Barrie in what was then Oro Township on March 21, 1992, eventually leading his daughter down her own path of justice.

The elder Kneeshaw was a successful entrepreneur who ran a series of bingo halls, had a gravel pit and a classic car collection and was active in the community through the Civitan Service Club, which held a memorial service in his honour and started a scholarship in his name.

He also clung to his farming roots. He often wore a flannel shirt and work pants, and had what his daughter describes as a diligent work ethic which he tried to pass on to his children while working on their small Oro farm.

"The day of the tornado of 1985, my dad jumped in to help. He took an injured person to the hospital using a door from the debris as a stretcher in the back of his truck," she recalls. "He worked tirelessly that day helping people and trying to clear out debris. He took loads and loads of debris from the in the back of his truck and dumped it in the gravel pit to be disposed of later.

"He had so much more to teach me and I wasn’t done learning yet. So many times over the years, I wonder how different our lives would have turned out had Dad lived. We all loved him so much and his loss has left a huge hole in our hearts."

His best friend and sometime business associate Jack Heyden, along with his son, Bill Vanderheyden, were convicted of first-degree murder in 1999 — a verdict that was overturned by the Ontario Court of Appeal after they spent a decade in prison.

They both then pleaded guilty to lesser charges. Heyden pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit murder, while Vanderheyden pleaded guilty to being an accessory after the fact. Both were sentenced to time served.

With Vanderheyden’s death at the age 57 earlier this month, following the death of his father three years earlier, the final chapter of their decades-long saga is written.

For Kim Kneeshaw, it seemed time to share her own story of a life forever changed by a tragic loss.

She was 27 when her dad was killed nearly 30 years ago, so she’s outlived him, as did Heyden and Vanderheyden — people she knew at the time as family friends.

The Heydens were friends for as long as she could remember and the kids would play together when they were younger while their parents visited.

So in 1994, when the father and son were charged, the young Kneeshaw was shocked and asked the lead OPP investigator if he was sure.

By the time the 18-month trial finally concluded with a guilty verdict in 1999, Kneeshaw was convinced the police did catch the right perpetrators, an opinion that hasn't changed over the years despite the protestations of the convicted men.

And she was happy that her family didn’t have to endure the experience of another trial, even with the truncated sentence the men received resulting from the plea deal.

Several years after the verdict, a three-member Ontario Court of Appeal panel had found the trial judge erred in refusing to permit the defence to challenge the credibility of three “unsavoury" witnesses. Their testimony that Heyden confessed to the murder ended up becoming the basis for the successful appeal to have the murder conviction overturned.

“By the time that they were finally granted an appeal on those grounds, it was nine and a half years later, there were witnesses that at that point were dead, they were not available. And my mom was sick... and I was terrified that the stress of a second trial would cost me both parents,” she says.

The case itself was circumstantial, resulting in the longest jury trial in Canadian history at the time.

And for Kneeshaw, it was many things — awful and at best uncomfortable.

She recalls sitting on a bench in the hallway of the courthouse waiting to go into the courtroom to testify and becoming engaged in a conversation with another young woman there.

“We were both moms, we were chatting. I had no clue who she was,” says Kneeshaw, who later discovered it was the wife of the younger man accused of killing her dad. “It was like, 'Oh, that’s weird.'

“I don’t think she knew who I was, either. … I felt very badly for her and the kids, really. It’s not her fault — she didn’t have anything to do with it. She’s very much a victim of this situation as anyone else.”

In 1999, as the murder trial dragged on, a new organization started developing in Orillia. Kneeshaw participated in North Simcoe Victim Services’ first volunteer training program that spring.

Her dad’s death and the experience of the trial "100 per cent guided my decision to join victims’ services, because I wanted to be able to support other people” who may have lost someone and need guidance, she says.

While there are witness and victim support services at the courthouse, the service that attracted Kneeshaw was designed as a crisis intervention program.

With volunteers available around the clock throughout the year, North Simcoe Victim Services provides immediate practical and emotional support to victims of crime or tragic circumstances.

“It means so much to have someone sit beside you and maybe pat you on the arm. Just to have someone there, to know that somebody else cares about what’s happened to you,” Kneeshaw says. “It makes a difference just to have somebody there.”

The volunteer training, she says, exceeds government standards and, for some, has been a life-changing experience, leading to transferable skills. Many volunteers, like Kim Kneeshaw, have had traumatic experiences.

What a difference it would have made to her family, she says now. They had questions no one had the time to answer, no link to information and they all needed some kind of emotional support.

“Sitting and helping people make a list of who they need to call, supporting them through those calls. And, honestly, just knowing that somebody cared enough to come and sit with you,” says Kneeshaw, who, at the time, had been involved with the family businesses.

After her dad was killed, the business continued but in a smaller capacity. Kneeshaw found herself more drawn to victim services, serving as a team leader. While scheduling staff for the business, she was also scheduling 45 volunteers for 12-hour shifts, 24-7.

Four years later, she came on staff as volunteer co-ordinator. Now she continues with the organization as its executive director.

“It just became my life,” she says. “It’s a vocation, I don’t look at it as a job.

“I am very glad to see some of the changes that have happened and I hope that more come yet to assist more victims.”