A protracted court battle that finally came to an end this past week traces its roots to the persistence of a former patient determined to prove that the years-long experimental treatment involving mind-altering drugs, naked confinement and use of restraints had no scientific merit and should never have been condoned by the government.

On March 30, the Supreme Court of Canada announced it would not consider the appeal application by Dr. Elliot Thompson Barker, Dr. Gary J. Maier and the province of Ontario, finally closing the door on the case.

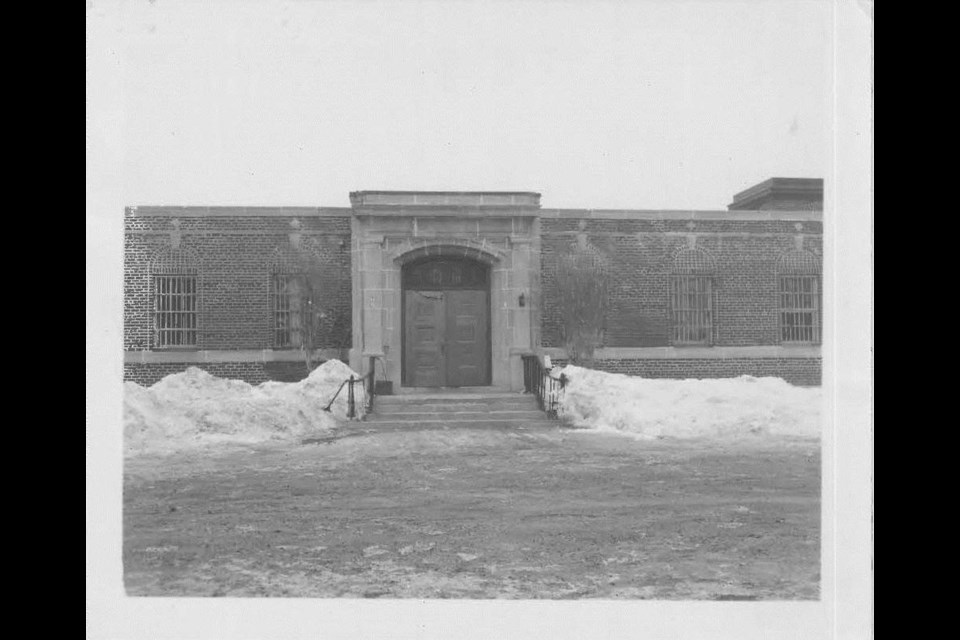

They must now pay the more than $9 million to 27 patients who endured experimental treatments between 1966 and 1983 at the former Oak Ridge, Penetanguishene’s maximum-security psychiatric facility, now the location of the Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care.

In his 2020 decision following a lengthy trial, Ontario Superior Court Justice Edward M. Morgan refers to the determination of one of the former patients, identifies as she or her, and credits her with exposing the program.

Her “persistent and thorough investigations” revealed that the experimental programs were “medically meritless,” he wrote in the 300-plus-page decision.

Morgan pointed out that the former patient shared her extensive research into the nature of the programs, the risks and resulting harms with some of the other patients in the 1990s. She then suggested they had grounds for a civil claim against the doctors and province.

The judge wrote that although some of the patients had previously alleged mistreatment at Oak Ridge in lawsuits, it was the former patient’s information that demonstrated that what they had thought was a medically sanctioned course of treatment was actually wrongful and actionable.

“Plaintiffs’ counsel submit that it was at that time that she uncovered documents and information relating to the nature of the programs, and started contacting her co-plaintiffs one at a time and eventually retained counsel,” the judge wrote.

The former patient, who is among the 27 plaintiffs listed in the suit, agreed to a phone interview providing her name and current living circumstances not be published as she vows to continue advocating on behalf of mental health patients.

“We were forced to undergo treatment, it was painful,” she said. “They used pain and coercion to get our compliance.”

She was committed to Ontario’s only maximum-security psychiatric facility in 1976, where she spent most of the next eight years. During that time, she was exposed to three programs developed by the doctors intending to assert control over the patients and change their behaviours.

The “defence disruptive therapy” program, or DDT, employed a mind-altering drug regime.

“The capsule” was a constantly lit room in which patients were sent for two weeks naked, taking in food through a straw in the wall. It caused the patients to become disorientated and disconnected from time in what the patient describes as a “rape of the mind” intended to prevent a more menacing rape.

Patients seen as defiant, unmotivated and not interested in participating in the first two programs were made to participate in the “motivation, attitude, participation program” or MAPP — described unanimously by the patients in their testimony as the most harsh.

“And that was the torture of torture,” recalls the former patient. “They put me through hell in that program, because I didn’t want to go along.”

In a 2003 affidavit, one of the doctors referred to it as being educational rather than punitive, intent on “re-orienting a group of disruptive patients when they were unwilling or unable to comply with their community rules.”

“A close look at the actual content of the MAPP reveals that the line between conveying a lesson and punishing a non-co-operative patient was so thin as to be invisible,” Justice Edwards wrote in his 2020 judgment.

The experience began with several days of solitary confinement in an unfurnished cell. Patients slept on a raised cement platform and they had no clothing, wearing only a heavy sack gown. They were deprived of any outside contact for three or four days, and were then placed in a group setting in which they could earn “privileges,” such as wearing clothing or being given a cushion to sit or lie on.

The most painful for many was being forced to sit motionless for hours on a cold floor, which was described by one doctor as “positional torture”.

Having earlier fought the system, winning the legal right in 1983 for patients to review their own files, the former patient decided in the 1990s to research the origins of what she and the other patients had earlier endured.

She said that because of her earlier efforts, she was able to access files. What she discovered was the series of programs that continued for 17 years in Penetanguishene had no medical merit.

“This is a government-run facility; it’s called a hospital where they send people to get treatment. These treatments, when I read the research, were not even scientifically proven," said the patient. "There was no other comparable program in the research that I could find that would validate this as a legitimate program.

“It was an unscientifically proven program. And Dr. Barker’s research in 1968 and 1977 clearly indicated that only upon release will we know if the programs worked or not. And they didn’t know how the person would work out in the community, but they let us go anyways. I was shocked," she added.

It was at that point, she recalled, that she became an activist, sharing her findings with others and setting out in search of a lawyer to right the wrongs done to the patients, using the law to improve mental health treatment.

She landed on Joel Rochon, who had just co-founded Rochon Genova LLP in Toronto.

"I was in total disbelief at the bizarre nature of the story (she) was relating to me,” he wrote in an email. “But I was also struck by her photographic recollection of the programs — the Capsule, MAPP and the DDT — this was not something that could be made up.

“Our initial discussions by telephone transitioned to in person meetings at Oak Ridge, where our legal team met with each of the plaintiffs who were still there, and learned of the extreme suffering they had endured while held at this maximum-security psychiatric hospital," Rochon added. "This was the very same building that had earlier housed the social therapy program.”

In addition to providing her accounts through interviews, the former patient presented detailed binders of documentation on the programs that she had unearthed.

That helped supplement the 100,000-plus pages of clinical records Rochon's team eventually obtained from the government as part of the documentary production process.

Meanwhile, the former patient pledges to continue in hopes of seeing much more change and says the 27 patients should take pride over their recent success through the courts. But, she added, she will never recover from her experience at Oak Ridge, which offered the patients no lifeline during her time there.

“It was wrong. And I’m glad they didn’t get the leave to appeal, because they were wrong all the time," she said. “I breathe and live to right the injustices — it’s not over. There are wrongs continuing to happen in the mental health system. Positive changes are coming and we’re on top of it.”

She was among the Oak Ridge patients sent to St. Thomas Psychiatric Hospital in the late 1970s, which has become the subject of a proposed class-action lawsuit.

The Toronto law firm that represented the Oak Ridge patients alleges that a parallel “operation of a medically meritless, experimental patient-run program” was implemented in the southern Ontario facility.

The basis of that proposed class-action lawsuit involves the use of male Oak Ridge patients — who suffered from serious mental illness and had committed violent, including sexual offences — to operate another social therapy program involving mentally ill female patients held at St. Thomas.

Lawyer Golnaz Nayerahmadi, who was on the legal team acting for the Oak Ridge plaintiffs, stressed that all Canadians, no matter where they are or what they’ve done, are owed basic rights, including those at Oak Ridge, which housed some of the country’s most dangerous men.

“These clients are mentally ill individuals in these forensic hospitals and sometimes what’s lost in these cases, regardless of their diagnoses and their background and histories, they all have and are entitled to certain rights,” Nayerahmadi said. “That’s often forgotten in these scenarios, whether government facilities or professionals (who have) immense amounts of power and control over their treatment.

“For a court to confirm what they went through was wrong is really important to them I think," she added. "It’s hearing it from that source of authority … because it was an authority figure that subjected them in the first place to this.”

The former patient insists: “It’s not over."