Newly uncovered documentation sparked a crucial question for author Mary Ormsby: Was Ben Johnson denied due process in Seoul?

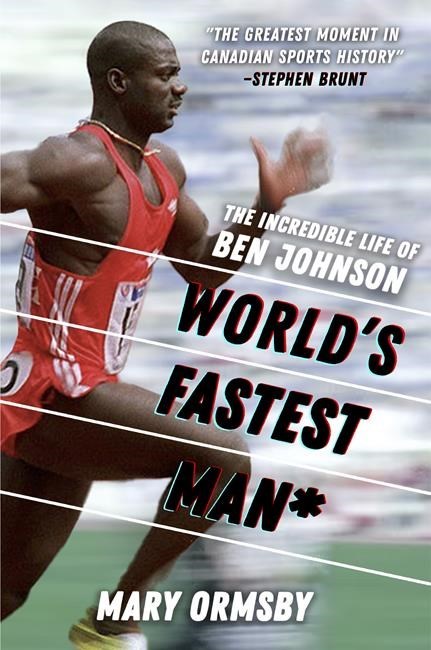

While researching her new book, "World's Fastest Man: The Incredible Life of Ben Johnson," released on Tuesday by Sutherland House Books, Ormsby unearthed details that led her to consider a new perspective on Johnson's story.

“We could probably tell his story in a way that would correct the historical record and shed new context on his treatment,” she said. “Maybe make us think differently about his particular case and doping in general, and that was kind of the genesis of the book.

“Also asking the question, is it possible to railroad a guilty guy?”

The book details Johnson’s life in Jamaica, his birth country, where he was one of six children to Ben Johnson Sr. and Gloria Johnson, as well as his immigration to Canada in the spring of 1976.

Ben Jr.'s older brother Eddie introduced him to the Scarborough Optimists track club, where he was first coached by Charlie Francis in 1977.

That was the beginning of a successful partnership between Johnson and Francis that lasted over a decade.

Her book delves into Ben Johnson's initial steroid use in late 1981, the era's lax doping control, the widespread doping prevalence in the 1980s, and the methods used to evade and mask positive tests.

It also recounts the pivotal days in Seoul, South Korea, during the 1988 Summer Olympics, when Johnson's positive test for the anabolic steroid stanozolol, after his record-breaking gold-medal win in the men’s 100 metres, changed history.

His gold medal was stripped, and the world record was wiped from the books.

“I really feel Ben was singled out for a lot of reasons, but in Seoul, he was the only track and field athlete to test positive,” said Ormsby, a former reporter with the Toronto Star. “One guy. And that I find puzzling because this was supposed to be a state-of-the-art drug lab with the smartest scientists, and they're going to catch all the bad guys and girls.

“In the years later, we would find out that six of the eight men in that 100-metre final are linked directly or indirectly, to doping violations.”

In her book, Ormsby recounts several instances where this was evident.

Ormsby wrote: “Not only was Ben Johnson’s detailed lab report withheld by the IOC medical commission, but a second similar event occurred that same night in Seoul. An additional doping screen was conducted on the runner’s urine sample without his knowledge or consent. It was the endocrine profiling test, a pet project being developed by (drug testing pioneer) Manfred Donike.”

She added: “Neither the test’s existence nor its results were disclosed to the Canadians in advance of Johnson’s hearing in Seoul. Endocrine profiling was not an authorized IOC anti-doping tool at the time. What’s more, endocrine profiling had never before been used to confirm a positive doping result. Johnson was singled out as the lone athlete out of more than eight thousand in Seoul to be subjected to the test.”

Ormsby also highlighted "unusual aspects" of Johnson’s lab reports in the book, noting that no one in the Canadian group complained about the lack of disclosure or challenged the validity of this new test.

“Unsigned handwritten alterations riddle the thirty-one pages — a series of revisions, deletions, question marks, switched lab codes, calculation doodles, and, oddly, the name of a different anabolic steroid, oxandrolone,” she wrote. “The records of an IOC-accredited lab were expected to be of the highest integrity and beyond reproach.”

A deep dive into Johnson's return to track and field years after, and more sanctions that followed, are also detailed along with his life off the track and into his retirement.

In between all of that, however, is a behind-the-scenes look at the famed Dubin Inquiry, which opened the public’s eyes to the world of doping in sport, alongside the backlash Johnson faced alone and the many who turned on him as a Canadian, calling him Jamaican instead

“That's an important part of the book because Canadians think they're very, very tolerant,” Ormsby said. “And in this case they weren't. … So the backlash after his disqualification was severe and harsh and there was a lot of racist comments about him.

“The Canadian government also stepped in and said you are banned for life, you will never represent Canada again at a national team level. So all of this helped define this very crushing moment for him.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 16, 2024.

Abdulhamid Ibrahim, The Canadian Press