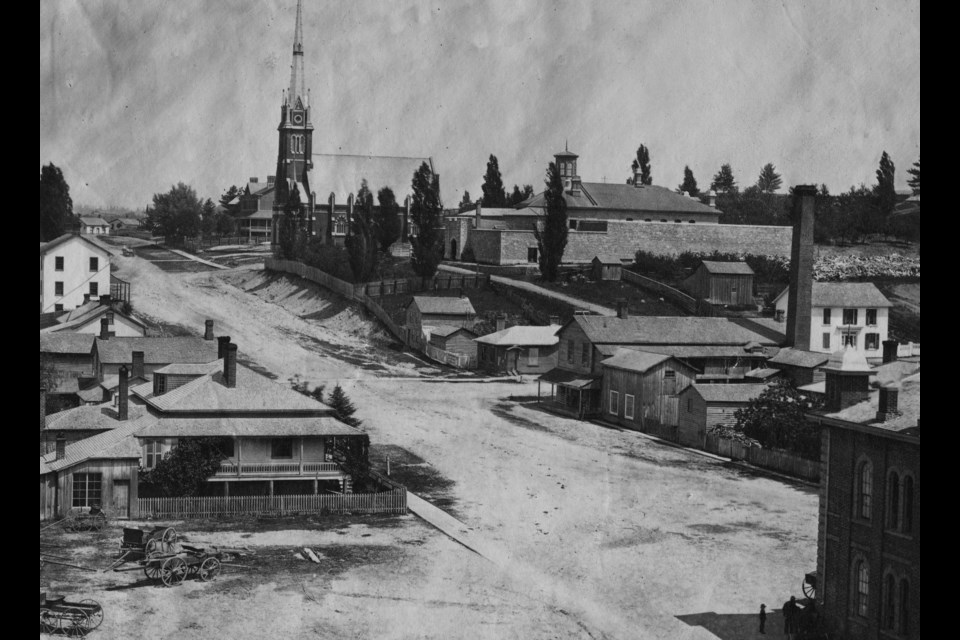

Barrie might not be the city it is today if not for one decision made almost 180 years ago.

That was when the little village by Kempenfelt Bay was chosen to be the political centre of Simcoe County.

Su Murdoch, a heritage consultant based in Barrie, says the building of the Simcoe County Jail (sometimes referred to as the Barrie Jail) and the adjoining courthouse led to the city’s growth.

“It relates to the fact that Barrie was selected as the the county administrative centre,” she says. “The requirement for that was they had to rally to build the court house and the jail before the official declaration in January 1843.”

Getting that meant that Barrie would survive, she adds.

“The Nine-Mile Portage was closed; the town didn’t have running water so it wasn’t a big industrial sector (at the time). It was live or die,” Murdoch says. “Getting that appointment from the province was very important to Barrie’s future and those two buildings (for the jail and the courthouse) were part of the requirement.”

The design of the former jail on Mulcaster Street is in keeping with the architectural psychology of jails (in regards to incarceration) at the time.

“It was an octagon with two wings; if you imagine a head of a bunny,” she chuckles. “That was the shape of it.

“That was the current thinking on jails.

“They actually toured to a lot of places, including the United States, to see what was the best design and hired an architect to do it.”

It is constructed of locally-quarried limestone and designed in 1838 by Toronto architect Thomas Young, who was also designing a jail for Huron County in Goderich and a jail and courthouse for Wellington County in Guelph, Murdoch says.

She says it was a long time before the gaol (the original spelling of jail) even had prisoners in it. The building’s first role was in regards to social housing.

“What do you do with homeless, starving people?” she asks, adding that a social safety net had yet to be developed.

“Somebody who had no place to go got ordered to go somewhere and ended up in the jail, not because they got arrested but it was a place to ‘park’ them,” Murdoch says. “There were children, women; there were drunks, there were homeless who were living there for a long time before anyone was incarcerated.

“I’ve been in the jail (not under arrest!) and I wouldn’t wish that on anybody. It is incredibly small and standard for the day.”

Of course, what’s an old ‘gaol’ without a good, old fashion hanging. The last of five people who went out on the end of a rope was in 1945.

“We’ve always believed they were buried in the courtyard at the jail. I don’t know if there has been thermal imaging done (to find the remains) or not,” she says.

The building was closed to prisoners in 2002 with them being sent to the Penetanguishene 'superjail’.

The current use of the building is in a holding pattern, she says, adding the courthouse had offices in it for time.

“It’s owned by the province,” says Murdoch, who was part of the feasibility study for the jail. “The protocol is, the province owns it and the province will offer it to the most relevant ministry: Correctional Services or the Attorney General will have the next take on the building if they want it. From that it will go out to any other ministry and if that is a no go, it will be up to the City of Barrie.

“And at that point if the province wants to divest itself of a heritage building, there would probably be some other protocol. It’s on the provincial registry of heritage assets. It is categorized by the province as a heritage building,”

Murdoch says as far as she is concerned the almost 180-year-old building should remain.

“It’s absolutely got to stay; it’s a landmark,” she says. “It’s an important building to Barrie and to the province and an extraordinary building of its time."