This column examines the Quaker pacifist influence in Ontario, its origin and effect on our history.

Quaker or Friends pacification has become one of the known facts in our rich local history, so I wanted to examine it further.

Quaker pacifism finds its roots in 17th-century England, but it continued to flourish and expand once the Quakers arrived in North America.

In 1661, the Society of Friends presented the following declaration of conscience to King Charles of England.

“We utterly deny all outward wars and strife and fighting with outward weapons, for any end or under any pretense whatsoever. And this is our testimony to the whole world. The spirit of Christ, by which we are guided, is not changeable, so as once to command us from a thing as evil and again to move into it, and we certainly do know, and so testify to the world, that the spirit of Christ which leads us into all Truth, will never move us to fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the Kingdom of Christ, nor for the kingdoms of the world.”

War and strife followed the Friends to their new home in British North America. They were hard-pressed to maintain their non-compliance with war and its mechanisms, often causing stress. While various internal differences eventually divided and reduced their membership, the Quakers’ commitment to peace remained constant.

During their early years in Upper Canada, their focus was on philanthropy and the avoidance of military service. During the early 20th century, they turned to their conciliation skills to reinforce their firm belief in the uselessness of war and to influence and address the causes of war. The historical development of the Society of Friends in Ontario has promoted political conciliation, pacifist activism and the promotion of arbitration as a route to peace.

For more than 150 years in Ontario, the Quaker structure and principles have led them into a leadership role in the promotion of peace. The fundamental ideals of opposition to war are both religious and ethical in nature. An intrinsic part of the Quaker belief system is the process of consensus among all parties.

The first American Quakers who settled in Upper Canada in 1784 (including my Lundys kin), and those who followed, were part of a greater migration of Americans, lasting until the 1820s. Some pro-British Quakers fled the United States to be free of political persecution and post-revolutionary economic hardship.

Although not technically considered United Empire Loyalists, the Quakers were invited and welcomed to Upper Canada by Lt.-Gov. John Graves Simcoe because of their qualities of honesty and hard work, as well as their sense of community building.

A few American Quakers had fought for the British and lost their Quaker membership as a result.

Simcoe would have preferred to have populated Upper Canada with members of the Church of England, thus furthering British ideals of a strong militia, but insufficient numbers of Anglicans were available. He decided to entice the various American peace sects, including the Quakers and Mennonites, to Upper Canada with promises of British law, an abundance of land, and respect for their pacifist ideals.

These ideals were reflected in the Militia Act of Upper Canada of 1791, which excused the peace sects from military service, but in lieu of bearing arms, the law imposed a tax on all military-aged objectors. The Quakers’ religious principles made the payment of these levies — paying money for the support of war — tantamount to their supporting war.

Refusing to pay the tax, their goods were frequently seized and sold to cover the amount of the tax. This prompted ill will between the Quakers and the government, with the Quaker leaders reasserting their principles of non-compliance.

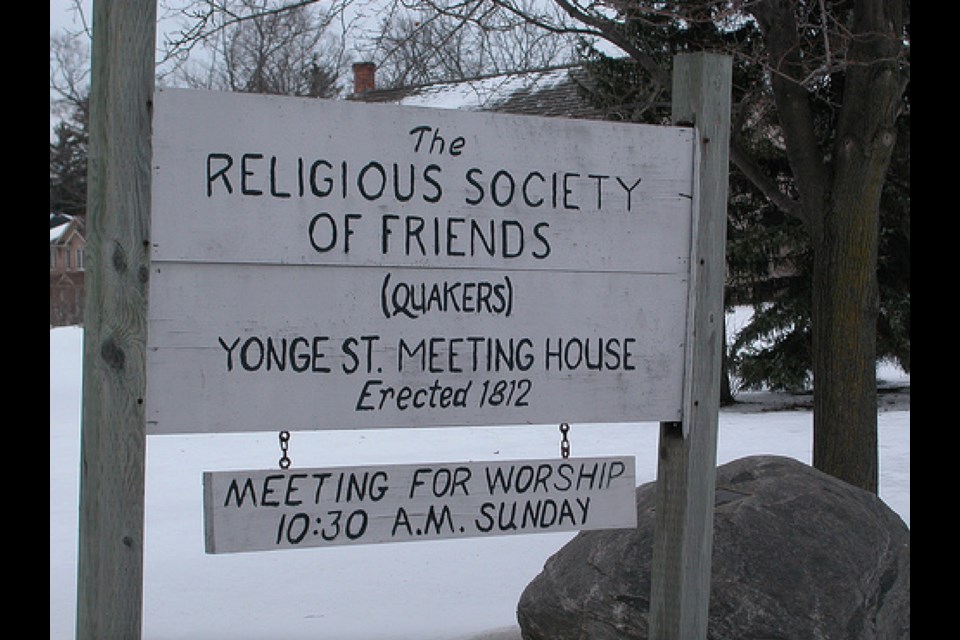

In 1806, Timothy Rogers and Amos Armitage of the Yonge Street Monthly Meeting met with Lt.-Gov. Francis Gore, reconfirming the Quakers’ loyalty to the existing government and their firm opposition to war. Gore stated his support and acknowledged the Quaker peace testimony. Nonetheless, in 1809, a law was passed authorizing military officials to repossess horses, carriages, and oxen to be used for military defence and imposing jail sentences on religious objectors who had not paid their tax in lieu of military service.

Men from our Yonge Street Monthly Meeting, located on a military road (Yonge Street), were regularly jailed, or went into hiding to avoid imprisonment.

Friends’ records indicate they would suffer confiscations estimated in the thousands of dollars. This would result in a strong, active lobby by each of the peace sects for the repeal of the 1809 statute, prompting the governing class of Upper Canada, during the War of 1812, to suspect all American immigrants of disloyalty to the Crown.

Local settlers felt threatened with the loss of their land, while others lost their right to vote and to hold office. Despite both physical and emotional hardship, area Friends refused to be co-opted into this war effort.

Soon, members found themselves embroiled in an armed political conflict with the governing class of Upper Canada (Family Compact), ultimately having an unsettling effect within the local Quaker community.

In a previous column, I spoke of several young Quakers who decided to participate in the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837 and 1838. After years of intimidation, Quaker peace principles were put aside owing to the social and political injustices. A few of these Quakers, including several of my relatives, who became involved in the insurrection were subsequently caught and served prison terms or were hanged for treason.

What was the reaction within the Friends’ community? Those who did not repent for the bearing of arms were disowned by their meetings. In response, some groups withdrew from any external influences, bringing about a period of relative calm.

In 1849, the three peace sects received a blanket, unconditional exemption from military duty by the Government of Canada West, prompting a period of decreased political activism by the Quakers.

Throughout their history in Ontario and particularly in our area, the Friends have been active in the promotion of social justice. They took a leading role in the Underground Railroad and assisted the fugitives to adjust to their new lives in Ontario. They have advocated for equal rights, universal suffrage, prison reform, and the abolition of capital punishment, all part of their policy on peace.

Post-Canadian Confederation, in 1867, the Friends delivered a statement of the Quaker position on war, oaths and liberty of conscience to Gov. Gen. Charles Stanley Monck and Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, resulting in the new Canadian government reaffirming the Militia Act of 1849.

Quakers continued to lobby for non-aggression in all forms. In 1891, the Friends of Ontario became affiliated with the Peace Association of Friends in America, which historian Arthur Dorland called “the most important peace organization among Friends in the Western Hemisphere at the time.”

By 1895, the Quakers of Ontario favoured a policy of arbitration instead of war to settle international disputes. This shaped their activities in the wars that followed.

In 1899, Canada became embroiled in the Boer War, and the Quakers published a series of strong anti-war resolutions, along with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (whose membership included many Quaker women). They were labelled a small, ineffectual and unrepresentative body of agitators, chronic objectors, traitors and villains.

Undeterred, they continued to their denunciation and, post-war, established the Friends Association of Toronto and the non-denominational Peace and Arbitration Society, Canada’s first non-secular peace organization.

The society eventually attracted more than 1,000 members headed by Sir William Mulock, chief justice of the Ontario High Court of Justice. As a result of the influence of the Peace and Arbitration Society, the Presbyterian Assembly in 1911 condemned war as contrary to Christian morals.

In Ontario, principles of peace gained public support. It was still generally lamented that peace was “accepted generally as a beautiful abstract idea, worthy of realization, but impracticable, and that war as undesirable, yet necessary and practical.”

Some pacifists in Ontario believed war was inhumane and irrational and should be prevented, but sometimes necessary, while others believed war was absolutely and always wrong. Quakers and Mennonites believe war is absolutely and always wrong.

The Canadian Peace and Arbitration Society called for the celebration of 100 years of peace with the United States, and the observance of Peace Sunday to counter growing military propaganda. At Newmarket, in that same year, the Canada Yearly Meeting Committee on Peace delivered a resolution to the government and people of Canada, expressing “the earnest concern of Friends” that Canada should encourage peace and arbitration both nationally and internationally rather than increasing our expenditures and activity in preparation for war and so-called defence. It also suggested money appropriated for the military should be spent on the establishment of a Canadian Peace Commission to help eliminate distrust between nations and to help stem the tide of militarism in Canada.

Promotion of militarism in Ontario’s schools was strong as early as 1869. In my columns on Newmarket High, I pointed out cadet training had been instituted in Ontario in the 1880s and continued to blossom until it was cancelled due to public demand. Quakers contended militarism in schools should be supplanted by “intelligent teaching as to the terrible results of war economically and morally to a nation.”

In an earlier column on the history of Pickering College, I wrote about how the school, being a Quaker school, decided to suspend classes for the duration of the First World War and convert the facility into a war hospital, treating repatriated Canadian military personnel as part of their patriotic duty.

This ends my look at the history of Quaker (Friends) pacifism locally. In the coming months, I shall take up the topic again and look at pacifism and its place in our recent history.

Sources: Friends and Peace: Quaker Pacifist Influence in Ontario to the Early Twentieth Century by Lise Hansen; Canadian Friends Historical Association; The Quakers in Canada — A History by Arthur G. Dorland; History of the Town of Newmarket by Ethel Trewhella; oral history interviews conducted by Richard MacLeod; Quaker Pacifism in the Context of War by Emma Hulbert; photo, Quaker declaration, Canadian Quaker Library and Archive.

Newmarket resident Richard MacLeod, known as the History Hound, has been an area historian for more than 40 years.